The late 1700s and early 1800s saw the emergence in Western Culture of what came to be called Romanticism. This movement was marked among other things by a desire to reject the past and encourage a revolutionary spirit in all things. The French and American revolutions can be seen as taking part in this, and in the arts there was a break with the rules 0f classicism and an embrace of the passions and self-expression. The early and influential Romantic Jean-Jacques Rousseau famously said “I may not be better than other men, but at least I am different.” To be oneself and to be unique became central goals and values.

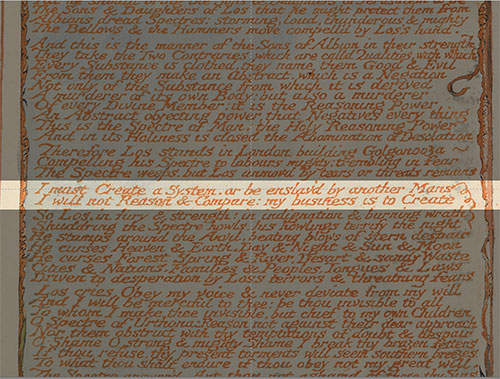

Two lines from William Blake’s Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion (1804–1820): “I must create a system, or be enslav’d by another man’s. / I will not reason and compare; my business is to create.”

With this came a desire among artists to be new and different, and to break the rules of the past. In England, for instance, the Romantic poets rebelled against the comparatively light and contrived poetry of the 1700s and moved toward more emotional and less formal verse. Despite breaking with the past, they did consider some of the poets from before their time to be great writers, especially Shakespeare and Milton. These became their inspirations, but their concern with being original made it problematic to imitate these precursors – especially such giants as those two.

In the 1970s literary critic Harold Bloom developed an interesting theory of how the romantics dealt with their indebtedness to past creators. Attempting to deny the influence these earlier poets actually exerted upon them, they ended up writing many of their poems as perverse, neurotic reactions to the great poems of the past. Because they didn’t want to be conscious of the pressure the past actually exerted upon them, they repressed their awareness of it. Yet their poetry actually reveals to the careful reader the traces of their subconscious imitations and echoes of past masters.

Bloom proposed an understanding of how these poets operated that was based on Freud’s Oedipus Complex. For Freud, the young boy wants to possess his mother, and as he starts to grow up, his father asserts control of his mother again. Consequently, the boy unconsciously wants to kill his father and replace him. Thus his father is both his rival and his model. He wants to be his father and take the place of his father.

Bloom argued that this was very similar to the relationship the Romantics had with their “strong precursors” – though they couldn’t consciously admit it, they wanted to destroy and replace the great poets of the past, and they did so in part by imitating them – in highly disguised ways of which they themselves were not conscious – in hopes of supplanting these great poets in the eyes of the reading audience (corresponding to the mother in Freud’s theory).

The idea of Anxiety of Influence is that the more one is concerned with being original, the more will be the subconscious pressure of the influence of the great artists of the past. Only ignorance of the past itself can relieve this anxiety. If one knows there have been artists in the past whose greatness is hard to come up to, one will find it hard not to imitate them in some way. So one tries to repress awareness of their influence, and this ends up with an unconscious and perverse form of imitation, much like how a boy will imitate (or rebel against) his father figure.

The imperative to be original remained important to many members of the avant garde until the middle of the 20th century, and trickled down into popular thinking, where being original, authentic, and unique were considered to be the marks of genius and integrity. In the 1960s, one was encouraged to reject the ideals of the past and “do your own thing.” Copying or borrowing from others was still largely considered to be lazy and unimaginative, and above all “inauthentic.” WIth postmodernism, the rise in remix culture (music), and then with the emergence of the Internet, however, the importance of being original has dwindled and the appropriative aspects of artistic creation have become increasingly legitimized.

If there were anything universally applicable in Bloom’s theory, we might expect today to see Jay-Z unconsciously imitating Tupac or Chuck D or Ray Charles or Louis Armstrong, but in a kind of twisted and hard to recognize way. I haven’t studied this myself, but I don’t think the Anxiety of Influence is much of a force outside of high culture – or even there, if high culture even still exists. On the whole, the Anxiety of Influence has become less intense in the postmodern period, in part because budding artists often haven’t even experienced or appreciated the greatest artists of the past enough to feel stressed by the challenge of living up to their greatness. Jay-Z probably doesn’t spend that much time listening to Beethoven, and if he does he probably doesn’t consider Beethoven to be in the same tradition as he is, a strong precursor, and he might not really appreciate how amazing Beethoven actually is anyway. It’s also unlikely that Jay-Z feels as much neurotic pressure to be original as the typical artist between 1700 and 1950 did; though he wouldn’t want to be caught dead stealing somebody else’s rhymes, presumably.

The title of Jonathan Lethem’s very clever and informative essay “The Ecstasy of Influence” is a take-off on Harold Bloom’s phrase that suggests the postmodern attitude toward originality. The idea underlying Lethem’s essay is that if we give up on being original and trying to outdo the geniuses of the past, we can all have a marvelous time just remixing the creativity of those who came before us. I’m not sure there are that many people still around who think such an attitude is a lazy, unimaginative cop-out.