Classical pianist Glenn Gould , the greatest Canadian (;-), was famous for his scorn of live performance and his embrace of recording technology. In one example of his use of the studio he spliced together material from two different takes to create one of the fugues in his recording of The Well Tempered Clavier. Although this kind of thing did occur in Classical music recordings, it was generally hushed up and reviewers and listeners found it disturbing, while Gould, in an essay from 1966, called attention to what he and the engineers had done and praised the superior interpretation created by electronic means. Gould loved technology and saw it as a positively liberating force for the arts.

The essay “The Prospects for Recording” was published in High Fidelity, a magazine read by audiophiles who mostly listened to classical and jazz records. Gould made several statements and predictions that were radical for his day, but seem to be borne out by the evolution of how we enjoy music since. Among his “radical” claims:

- Listening to recordings is better than hearing music live

- Privatised listening will take the place of public appreciation

- The roles of composer, performer, engineer, and ultimately consumer will be merged

- The audience will become the interpreter

Gould was convinced that this was the future: a world in which the consumer would take control of the listening experience, and ultimately of the interpretation. From the primitive controls on a home stereo in the 1960s, where bass and treble could be adjusted, but little else, Gould extrapolated a world of editor-listeners, in which the roles of composer-performer-critic-consumer were collapsed into a radically democratized creative being. It’s a world we’re on the brink of today.

It’s beginning. In an experiment applying his techno remix and sampling skills to the Classical realm, Stefan Goldmann has released a re-edit of Stravinsky’s Le sacré du printemps. Gould, I am sure, would have been fascinated by this interpretation, which previously existed in no concert hall or recording studio, but solely in the mind and laptop of Stefan Goldmann. Making use of material from fourteen different recorded versions of Stravinsky’s work, Goldmann creates an entirely new performance, which swoops from one mood and tone to another in a way that no living orchestra could. I can’t really judge whether it’s any good; I didn’t know the piece well enough before listening to Goldmann’s version, and it seems to me that it is by nature a disjointed and discontinuous sort of experience, even when it’s only being performed by one set of musicians.

But the potential for creativity suggested by this release is staggering. I want to be able to easily edit together the bits of performances that I like. In the process I can even edit out passages altogether or add new ones, creating music that Bach or Stravinsky never wrote themselves, for instance. The tools for this kind of work, still crude but getting easier to use and more sophisticated all the time, are basically already available.

The high-art bastion of Classical music has been surprisingly ready to give in, initially to professionals like Goldmann, or Carl Craig and Moritz von Oswald to whom no less an institution than Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft released the master tapes for recordings of Bolero and Pictures at an Exhibition to be remixed into an ambient audio tapestry of sorts. But it’s only a matter of time before it becomes easy for anyone with a computer to create their own interpretations and performances and adaptations of the music that already exists, as well as making music that doesn’t yet exist even more easily than they already can. Imagination will be the only limit, and in a world of non-destructive editing nothing will need to suffer at the hands of this creativity.

Orson Welles once said something along the lines of “A movie studio is the greatest toy a boy ever had.” We now have something getting closer all the time to this powerful toy at our fingertips.

Music is the flagship art in this movement. The tools that were starting to become common in the studio in the 1960s are now available, along with a myriad of others, in cheap or free software. The means of creating sophisticated, complex art that would in the past have required the cooperation of an orchestra and a recording studio are now in the hands of virtually anyone who has access to a computer. And the means of promulgating and promoting one’s creations or interpretations are also increasingly cheap and easy to master. Where music has gone, film and the other arts will no doubt follow.

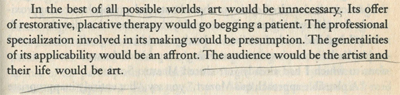

Gould concludes the essay with nothing less than the assertion that art as we know it will be unnecessary when people have complete access through technology to the means of creating and shaping their culture :