A form of cultural appropriation in which historical cultural contexts are ignored in favour of suggesting that current cultural norms have always been present, or are more valid than the context of the original.

This is a form of anachronism and decontextualization, and at times it could even be viewed as recuperative since it could remove any oppositional potential still to be found in historically remote works in order to bring them in line with mainstream values and ideas today, and suggest that those attitudes are eternal and natural.

Consider the beautifully rendered mashups of famous Western art masterpieces by Olivia Muus, “Museum of Selfies” from 2016.

Olivia Muus, Mona Lisa and The Girl with the Pearl Earring Selfie (2016)

These digital montages are superbly done, and it could be argued that they might work to interest people in classic art by suggesting that the figures in them are as interesting as the subjects of selfies in one’s feeds. But they also have the effect of insinuating that the subjects of these paintings were just like us, and took part in their own version of the pervasive spectacle of narcissism and self-publicizing that is so prevalent in the selfie-lebrity media of today. That “selfie” attitude toward the self – as an object for self-promotion through the mass media – was obviously not present in most (perhaps any) of the original subjects of the paintings repurposed by Muus.

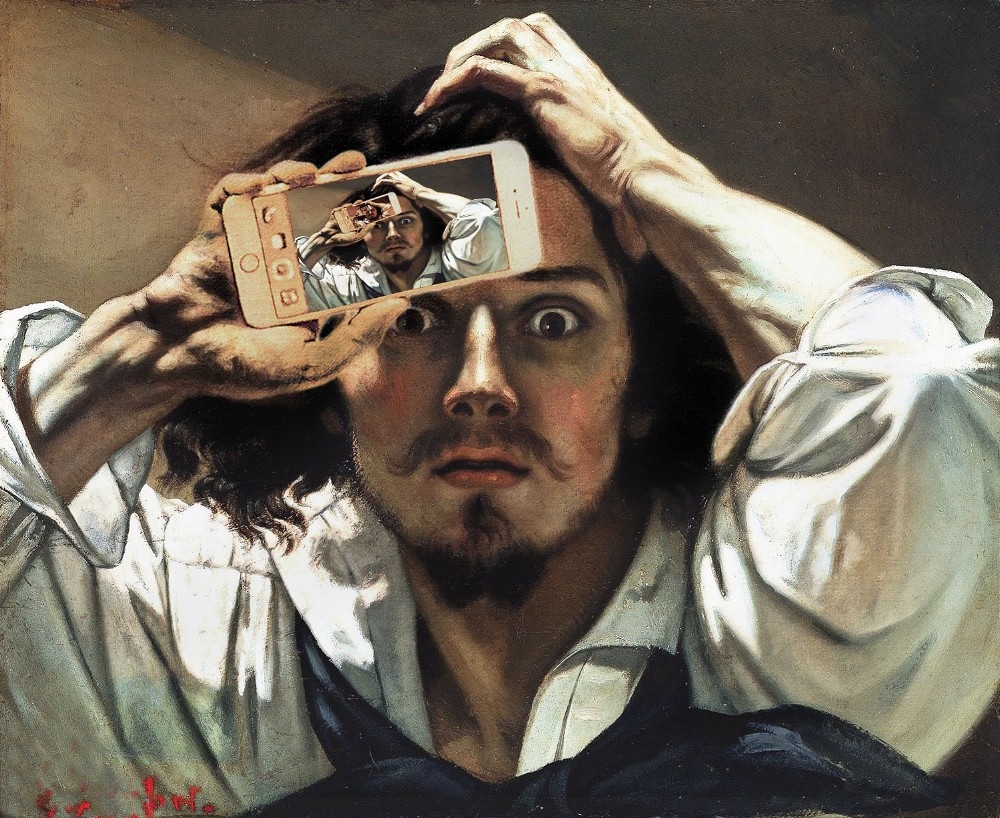

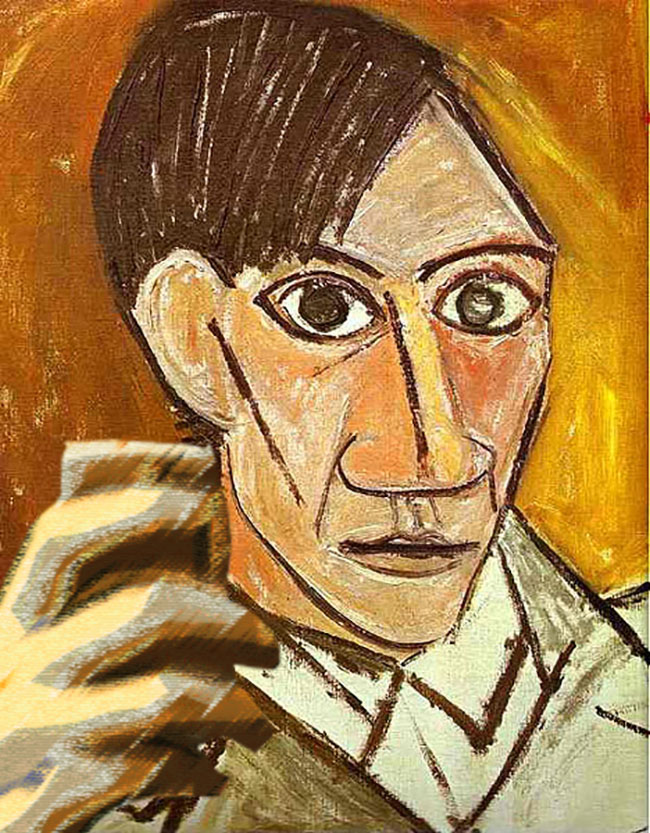

Some of Muus’s selfie edits are really fantastic looking. But only two of them were anything like a “selfie” originally, the artist Gustave Courbet’s The Desperate Man (1843–45), a self portrait of the artist, and Picasso’s 1907 self-portrait.

Olivia Muus, Man taking a Selfie in a Courbet Painting (2016)

Olivia Muus, Picaso Selfie (2016)

Muus’s title for the Courbet remix, “Man taking a selfie in a Courbet painting” makes one wonder if she was even aware that “The Desperate Man” was a self-portrait.

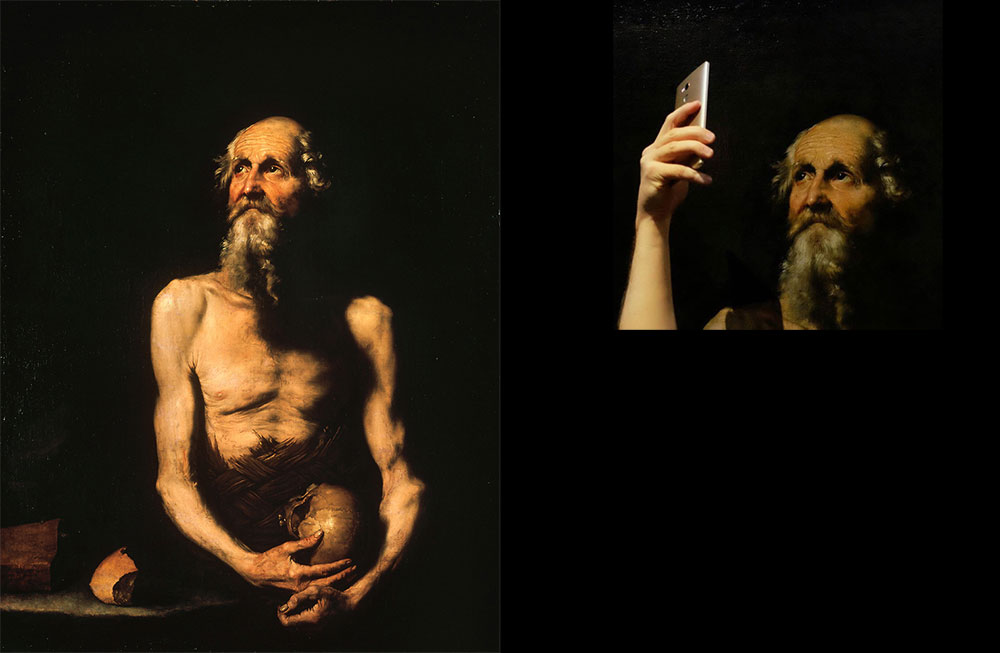

Other paintings in her series present subjects taking selfies that could hardly be further removed from our world of narcissistic self-promotion. Consider, for instance, her take on Jusepe de Ribera’s St. Paul the Hermit (1647).

L. Jusepe de Ribera, St. Paulus Eremita (1647) x R. Olivia Muus, Selfie Paulus Eremita 1647 (2016)

de Ribera’s painting represents St. Paul living alone in the wilderness, far removed from the rest of humanity. He holds a human skull in his hand. Such a skull was known as a memento mori (“remember that you will die”), and was a common motif in Renaissance art. The skull is meant to humble a human being, reminding them that this world and its honours are transient. Living as a hermit was a way people avoided the distractions of society and anxiety about things like status in order to get in touch with themselves and God. Muus’s replacement of the skull with a cellphone could be considered bitterly witty, assuming she was aware of all this; but unless a viewer is fairly well-educated and has some historical savvy they will more likely just think the image suggests that anyone appearing in a classical painting was as hungry for celebrity as our current selfie-lebrities are.

Such images are thus de-historicizing and, because they are so often made by people who know little to nothing about the original contexts of the art works, typically decontextualizing. They give a false sense of historical continuity and the normalcy of our own attitudes toward the world today. In fact, our own attitudes toward the world, ourselves, each other, and what matters may be as weird, and will almost certainly be as short-lived, as all of the other ideologies that have seemed natural and eternal to human beings.

Historians and cultural critics sometimes refer to this anachronistic introduction of present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past as presentism. Presentism is another form of cultural chauvinism, the uncritical adherence to present-day attitudes, especially the tendency to interpret past events in terms of modern values and concepts. It is simply not true, for instance, to say “we have always been capitalists.”

The action of nowjacking usually differs from détournement – which also aims to repurpose old works to make them express new messages – in that détournement is trying to critique and change our current culture and society, while nowjacking tends to re-affirm its legitimacy and suggest that it has always been like this.

See also détournement, recuperation, cultural appropriation, postmodern decontextualization