WEEK 09: détournement AND CULTURE JAMMING

QUICK REVIEW

Just memorizing the words in this box is not the same as understanding the material well enough to use it in the world, or to do well when you are tested on it. Some of this material is explained in depth starting at the left of this box, or on the main study site.

- The Society of the Spectacle

The modern Western world seen as a consumer society in which most people don't just "consume" products, but also consume images at the expense of living their lives - for instance, watching a tv show as a passive spectator rather than doing something active or participatory like gardening or playing a game with friends with your time. The phrase was popularized by Guy Debord and the Situationist movement in the 1950s and 1960s. - Détournement

A Situationist form of remix in which the media of past or current mainstream culture is hijacked and taken in a new more politically progressive direction. - Culture jam

A more recent form of détournement in which the media of a dominant culture (corporate, entertainment, political) is appropriated and remixed to criticize and subvert the values and goals of that culture. - Recuperation

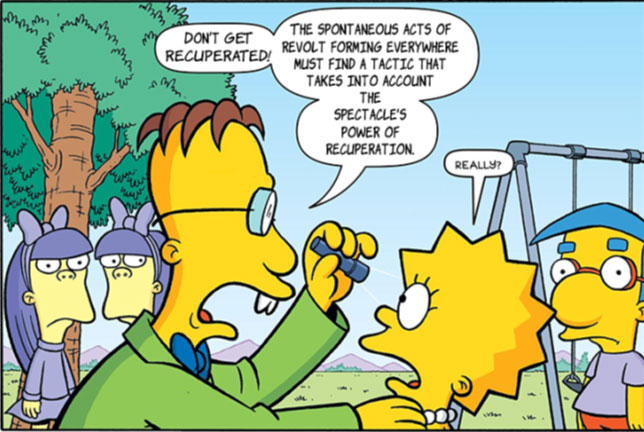

In cultural studies, "recuperation" is used to refer to the process by which politically radical positions, creations, and images are spun, taken over, absorbed, defused, and then commodified within mainstream commercial culture and bourgeois society. This turns them into part of the continuing Spectacle of the capitalist mass media machine, and thus these radical positions and views are interpreted through a neutralized representation that removes the anti-mainstream thrust or radical difference of the original. - Parody vs culture jam

See the detailed discussion on this page. - Brandalism

Creating sophisticated, comparatively subtle culture jamming signage in the public space

- Culture jimmies® and instajams®

Forms of détournement imagined by Dr Jim.

Culture jimmy a form of détournement in which signage and other public media put out by mainstream dominant culture are modified to use the slick or seductive or publicly prominent platform to send more progressive or disruptive “public service messages.”

Instajam is a method of guerilla détournement in which you deliver a culture jam or a culture jimmy by photoshopping it into a social media post. Also known as snapjam®.

This lesson looks at the question of whether the media of those in power can be remixed to undermine or criticize the values of the mainstream media created by those in power.

is it possible to appropriate the media of those in power to turn it back on them and fight the power? This lesson will look at that question and some of the more sophisticated answers that were proposed in the 20th century. In particular, I will be discussing the views of a group called The Situationists and their idea of détournement. I will also look at the more recent version of détournement that we find in the practice of culture jamming, and I will compare and contrast those ideas with the most common form of "critique" found in popular culture, parody.

The Society of the Spectacle

The idea of détournement was originated by an avant-garde artist group that was also a political activism collective. The Situationists arose in the 1950s and were most prominent during the 1960s and 70s.

The Situationists, inspired by Marxist and post-Marxist critiques of Western culture, argued that industrialization, consumerism, and new broadcast media had perverted human relationships in an unhealthy and unnatural way. Previously in human history, our relations had been directly with each other and with nature, but we now related with other people through manufactured objects and images.

For these critics, "All that once was directly lived has become mere representation" (Debord 1967). All human life is now mediated by products and unreal images. Consumer fetishes, brands, escapist fantasies, unrealistic materialistic ideals, partial images of reality created for the sake of entertainment or sensationalism - all of them manufactured for the rest of us by professionals working for companies who want to exploit us - had replaced authentic social life.

Guy Debord - the central Situationist - and his fellow activists believed that "everyday life"- life lived with other people doing meaningful practical tasks like making meals or working together - doing labour that was meaningful in itself, producing something of material worth (really material, not just symbolic), was the natural and most meaningful state for the human animal. They argued that with the industrialization of work and the invention of manufactured commodities, and the proliferation of endless images in mass media clogging any view of non-media reality, life had changed.

The emerging culture of television in the 1950s, which encouraged people to forgo social relationships in order to sit at home on their couches and watch packaged human interaction as a "show," had brought about the emergence of a "Society of the Spectacle." We no longer engaged in life directly and participated in society out in the world: we sat back as spectators in our living rooms and consumed the life that was projected on our screens for us by the corporations that create our manufactured media.

Before the triumph of the Industrial Revolution, most human beings had experienced life directly and participated in it. When we were done working for the day, we ate dinner together, talked, played games together, made music for ourselves, went to church, worked in the garden, went for a walk, and so forth. We participated in culture and nature.

In the 20th century, however, people living in the developed and wealthy parts of the world were able (and encouraged) to experience life in a passive and non-participatory way, through consuming film and broadcast media, television, advertising, brands, images. Instead of playing sports, we sat and watched spectator sports on television. Instead of making music ourselves, we listened to music made by professionals on records or on the radio. Instead of doing a lot of things we would have done ourselves in the past, we sat back and watched a manufactured spectacle of images of people doing those things (or simulating doing things) on screens for our passive entertainment. We could feel that "life" was not something we were subject to ourselves, but something we were disconnected from, in control of (as long as we had the remote). The mass media was a crucial part of the consumer society. We were not just consuming products; we were consuming images of life, often instead of fully living life ourselves.

The Situationists felt that the wealth of developed nations had led to a meaningless work life and alienated leisure time for the average human in those parts of the world. People's lives are filled with vicarious dreams of the "life" they see on television and in ads. The Society of the Spectacle contributes to the emptiness of modern existence, because it makes us passive, isolated and detached, inadequate-feeling, and driven to greater consumption and escapism, in hopes of somehow being "like the people on TV" rather than living our own real lives.

The Spectacle is the represented “reality” of the media in which we now all “live,” and at least when Debord was writing it was controlled by those in positions of privilege and power. Under capitalism, humans have gradually become passive consumers and spectators of the media, often treating real life as a form of media spectacle too, of which we are the passive observers. Nothing is real, everything is entertainment, and we live much of our own lives through this passive consumption of other people’s images. Everything that was once directly lived is now often experienced through representations of life, images.

Before industrialization and mass communication technology, we were focused on unmediated being and direct embodied social relations. Gradually we became convinced that having could and should replace being (consumer culture). And now we think what matters is appearing (appearing to be, appearing to have, being part of The Spectacle). This is the triumph of mainstream consumer culture over our very consciousness and sense of who/what we are as human beings. As the rock music critic Greil Marcus put it: “We are twice removed from where we want to be, the situationists argued – yet each day still seems like a natural fact.” We have gone from being to having (owning things) to appearing (displaying status through media).

Détournement

The Situationists encouraged public acts of resistance and public art, and they developed a form of "remix culture" they called détournement. The word is used to describe a creative appropriation that attempts to radically change the intended meaning or direction of the original work. For the Situationists, this means using outmoded or overproduced media to express new, more progressive values by remixing it. The Situationists were far left “art activists.”

The term détournement is French for “hijacking, diverting, changing the course of something.” Détournement as an artistic practice means “hijacking” the media of those in power or the established culture and turning it to a new meaning, one that is antithetical to, or at least not completely in line with the original intentions.

It also involves hijacking media that reproduces tired reactionary attitudes or values to give them a new, more progressive meaning; or hijacking media that presents a point of view that is largely unquestioned by the general public to throw it into question and make people think and feel about it again.

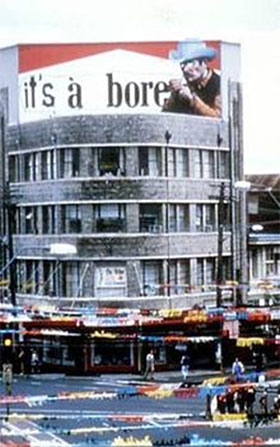

For example, in the early 1960s someone rearranged a billboard advertising Marlboro cigarettes. The cigarettes were seen as a symbol of masculinity, and masculine freedom -or at least they were marketed to people who wanted to have that image of themselves - for themselves and for others.

The vandalized billboard now said "it's a bore" trying to deflate the power of the and deride this symbol of masculinity and coolness. People who saw this billboard before it was fixed would have also had their easy consumption of consumer culture disrupted as they had to think about the sign and what it might be saying. This was not an attack on Marlboro the company, or even on cigarette smoking: it was an attack on the consumers and producers of a culture that lies and wants us to consume: products and images.

In 1956 Debord and Gil J. Wolman wrote a short “User’s Guide” to détournement that includes ideas like these:

The literary and artistic heritage of humanity should be used for partisan propaganda purposes. It is, of course, necessary to go beyond any idea of mere scandal. Since opposition to the bourgeois notion of art and artistic genius has become pretty much old hat, [Marcel Duchamp’s] drawing of a mustache on the Mona Lisa is no more interesting than the original version of that painting.

…

It is in fact necessary to eliminate all remnants of the notion of personal property in this area. The appearance of new necessities outmodes previous “inspired” works. They become obstacles, dangerous habits. The point is not whether we like them or not. We have to go beyond them.

What they are saying here is that the quality of works of genius - as much as commercial "art" like a Marlboro billboard - is not an excuse to leave them alone. All previous created work should be used as appropriate to push the world in a more progressive direction and away from the regressive emptiness of the Society of the Spectacle. The Mona Lisa is only a valuable source of détournement if it can be remixed to create a progressive, anti-consumerist, message.

The idea is a forerunner of Negativland’s Culture Jamming.

Culture Jamming

Culture jamming is a more recent emergence of these kinds of ideas, and it is clear from the way the creators of this remix genre talk about it that they are following in the footsteps of the Situationists.

A culture jam uses the media of a dominant culture (corporate, entertainment, political) to criticize and subvert the ends of that culture. Culture jams may be audio, video, or still images, and could possibly exist in other modes as well.

A culture jam is something more than a parody (of, say, an ad). Its intentions are to disturb you and your normal passive unconscious consumption of mainstream culture. See below under Parody vs Culture Jam.

A former student, Richelle James-Aikins, created the culture jam shown above, "Open Happiness." It cleverly uses the coke polar bear mascot to make its environmentalist critique of the climate damage caused by mass production of products like Coca Cola. The image is witty, but not exactly laught-out-loud funny, more disquieting. Culture jams are meant to leave you upset, not entertained.

Dominant culture typically aims at seduction, reassurance, a pleasing message, and to keep you unconscious of its “constructedness” (that it is not just the natural way of the world but something made up by people who want you to believe in it). Ads, for instance, aim to make you feel good about what they are showing you, and to desire it. For instance, a beer ad, two attractive young people, the girl in a bikini, everybody looking good and happy, familiar, nothing you need to think about.

Parodies tend to “laugh off” dominant culture stuff that we may not always be comfortable with, leaving it still accepted and normalized in our culture, though we have briefly recognized its falseness.

Culture jams typically try to be disturbing, upsetting, disruptive, leave you uncomfortable or even outraged. They want to make you feel different about the dominant culture.

Wikipedia:

Culture jamming is a form of disruption that plays on the emotions of viewers and bystanders. Jammers want to disrupt the unconscious thought process that takes place when most consumers view a popular advertising and bring about a détournement.

Activists that utilize this tactic are counting on their meme to pull on the emotional strings of people and evoke some type of reaction. The reactions that most cultural jammers are hoping to evoke are behavioral change and political action. There are four emotions that activists often want viewers to feel. These emotions – shock, shame, fear, and anger – are believed to be the catalysts for social change.

iPad culture jam

For instance, take a look at the culture jam at the left. Though clever and “funny,” it is more than a parody. It draws our attention to how “First World” the desire to have a thinner device is, and how useless such a thing is as a gift to an African (presumably) child who is dying from hunger. The intention is to make us feel guilty for our comparative wealth and to see our own consumer experience in a new, more viscerally real light.

There is more to it than that, for the informed viewer. The image could also be viewed as the starving African child giving the iPad to the person with the white hand. This might seem absurd unless you know something about the entire iPad manufacturing process. Many minerals are required to make an iPad, and these include what have come to be called “conflict minerals” (they include cassiterite (for tin), wolframite (for tungsten), coltan (for tantalum), and gold). These minerals are often mined in central Africa, and there have been many reports showing that they are often mined by children in forced labour camps, and the profits used to support arms purchases to continue conflicts in countries such as the Congo. Apple and other technology giants try to keep the dirty supply chain that often leads to your cool device from public consciousness, but there have been attempts to trace back the parts and labour to such appalling origins as the suicidal workers in a Chinese Foxconn campus and the war-financing human rights violations of forced child labour in Central Africa. For a viewer who grapples seriously with the image, there may be at least a small, genuine consciousness-raising experience in seeing this culture jam.

The term culture jam was coined by the artist collective Negativland to refer to their appropriative and countercultural take on the mainstream media. One of their best-known culture jams is Guns, which tries to make us see our fascination with firearms in a new way, and in particular how we pass this fascination on to our children:

You can watch other Negativland culture jams on YouTube, as well as Sonic Outlaws, Craig Baldwin’s 1995 documentary about Negativland and other early jammers .

The mashup documentary Rip! A Remix Manifesto (2008) discusses culture jamming at length. In this segment, Negativland’s Mark Hosler talks about why he thinks this kind of appropriation is legitimate. Part of his argument is that our public space is saturated with the messages of the mass media, and that we have no choice about this, even though the space should really be seen as a shared public commons.

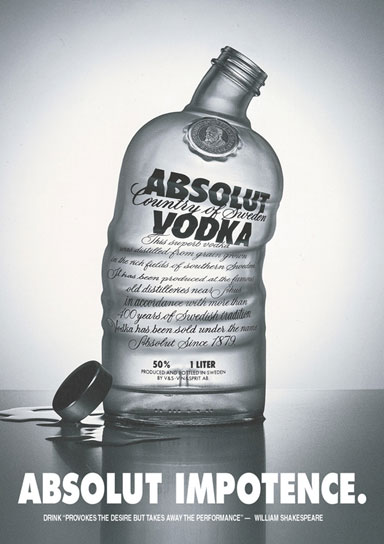

One of Adbusters's slick parodies of an Absolut vodka ad

Most culture jams end up being critiques not of specific politicians, parties, or products, but of consumer mass culture itself. A simple form of culture jam is to attack a well-known product to criticize the broader politics, morality, destructive values, unhealthiness etc of our consumer world.

Culture jams taking off on ads are sometimes referred to as subvertising. A franchise like Adbusters has capitalized on this kind of parody/satire/critique of consumer brands.

A basic form of subtervising is changing a company’s logo in a satirical way. Some people have started treating this as a form of meme hacking, because corporate logos are among the most widespread and recognized memes in our world (understanding memes in the broadest and original sense).

Though such take-offs can be funny and critical, many viewers will assume that the attack is on a particular brand, rather than on the whole way our world is currently commodified and marketed. For instance, people might watch Negativland's “The Greatest Taste Around” and think that the target is Pepsi, rather than the overall situation with junk food, seductive advertising, our addiction to both junk food and advertising media, etc.

Recuperation

Recuperation, in the technical sense, was the word the Situationists chose to refer to the process by which politically radical positions, creations, and images are spun, taken over, absorbed, defused, and then commodified within mainstream commercial culture and bourgeois society. This turns them into part of the continuing Spectacle of the capitalist mass media machine, and thus these radical positions and views are interpreted through a neutralized representation that removes the anti-mainstream thrust or radical difference of the original.

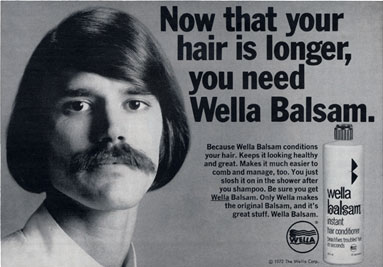

For example, when hippies were turned into a market and characters on sitcoms, and there were ads that said things like “now that your hair is longer, you’ll need a different shampoo!” Recuperation is cultural appropriation, taking ideas, images, themes, and works made by subversive countercultural forces and turning them into another aspect of commodified mainstream culture. Recuperation is thus the opposite or inverse of détournement, in which images and other cultural artifacts are appropriated from mainstream sources and repurposed with radical intentions.

In my life, I have seen many examples of recuperation. Whenever a band "sells out," whenever an oppositional music becomes mainstream (punk, hip hop) one could speak of recuperation. Looked at more positively, this sometimes involves the normalization and inclusion of a subculture within in larger culture - which can be seen as a positive. But it also tends to involve the emptying out of the radical content of the subculture to make it fit into the existing status quo.

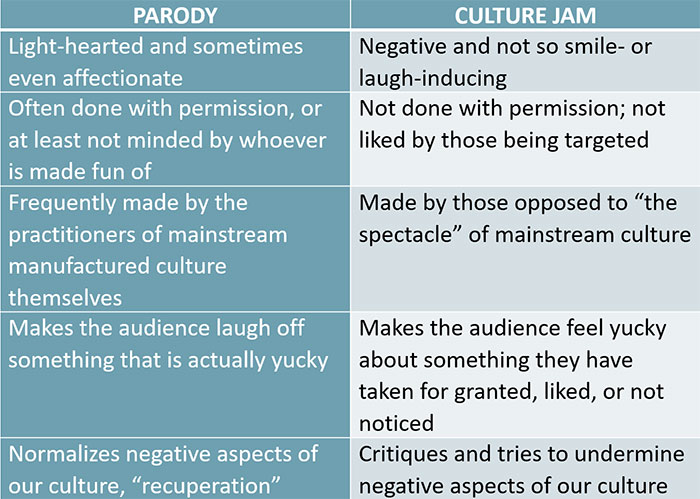

Parody vs culture jam

Parody is a weak form of critique. Its effect is typically to make us laugh off something we might actually think is wrong or bad, releasing our negative emotions in cathartic laughter. Parody is actually often welcomed by those it targets, because the parody nevertheless reaffirms them and their positions. Culture jams, on the other hand, excite only the bitterest laughter. They want you to feel differently about what they are appropriating and drawing your attention to. Parodies “make fun”; culture jams disrupt and upset.

Corporate Appropriation and Commerical parody

An example from the 2018 Super Bowl helps explain what postmodern decontextualization looks like, how parody is generally a weak form of critique, and what politicized appropriation looks like.

Background: The words being said by King in the ad come from a 1968 sermon called “The Drum Major Instinct,” which King had adapted from the work of an earlier writer. By “Drum Major Instinct,” King means our seemingly natural desire to be in the front of the line, at the top of the heap, Number 1. Against this view, King urges his congregation to embrace the humbleness of a servant. He bases this on an incident in the New Testament, where two of Christ’s disciples ask if they can have the seats of honour to the left and the right of him in the Kingdom of God. Jesus tells them it is not up to him to decide, but in any case they should be focused more on being servants (of God, or Good) than VIPs.

The use of King's sermon in the RAM ad shows an example of decontextualization, as King’s sermon is used out of context to sell trucks to Americans, as well as urging them to serve a in sense unrelated to God, for instance in the military, as fast-food servers, or serving the economy.

It is interesting - to repeat - that the makers of the ad have chosen words from the sermon that play up the value of serving, and added in images of their own to show whom they imagine being served. MLK had in mind serving God, the ideals of Christianity, or one’s fellow man. But the people we see in the ad are serving their country (military), industry (work), their families, the consumer culture, etc. Another part of his speech that they’ve chosen to give prominence to is the anti-intellectual declamations which – out of context at least – seem to validate the ignorance of the typical American (as long as they are “serving”):

You don’t have to know about Plato and Aristotle to serve.

You don’t have to know Einstein’s theory of relativity to serve.

You don’t have to know the second theory of thermodynamics in physics to serve.

You only need a heart full of grace, a soul generated by love.

Apart from trucks, then, it could be argued that the commercial uses parts of King’s sermon to encourage ignorance and servility, and that the imagery it employs pushes family values, hard work, and patriotism.

More background analysis: Though some of these would be in line with King’s own agenda in that particular sermon, they might be found less palatable by other African American activists. If Malcolm X had still been alive to hear King’s sermon, I’m sure he would have been disgusted to hear the emphasis on servility being presented in it, given the amount of servility that African Americans had already been forced or expected to endure during the 200 years of what he called “the American Nightmare” that had been unfolding since 1776. X liked to point out to Black Americans that Christianity had been given to them in part as a consolation for being slaves and subsequently lowly members of society, and to keep them happy in those role, since the Judeo-Christian tradition did much to glorify the weak and the disempowered, those who suffer or are enslaved (Israel, Jesus), and suggested that “the meek shall inherit the earth.”

Though King might have acknowledged his belief in the value of service and hard work, I don’t think he would have been happy to see his words used as a justification for the ignorance of the mainstream populace, and I’m sure he wouldn’t have appreciated the overtones of patriotism and consumerism in the ad. Many people found the ad unbelievably tasteless, and there was criticism in social media.

Parody

Stephen Colbert (who seems to have turned into Johnny Carson since I last saw him being clever) did a take-off of the ad a day or two after the Super Bowl that parodied the use of a spiritual leader selling trucks:

The Colbert Show, one might note, begins by showing the full ad so that people will be able to get their joke (did Dodge actually pay for this additional spot, perhaps?!) and then his comedy writers make another ad for the Ram, using the kind of dimestore irony that was being done on The Simpsons 20 years ago. Not sure what Dodge made of all this. No bad publicity? No bad complicity?

More radical détournement of the ad

But while network tv was parodying (and reproducing) the ad, an amateur culture jammer, Nathan Robinson, had already done a much tougher or more to-the-point send-up of the ad, not on television, but on YouTube: “What Martin Luther King Actually Thought About Car Commercials.”

Using other parts of the very same sermon, Robinson deftly brings back two of the main themes of King’s sermon completely ignored by the Super Bowl ad: the pernicious activities of advertisers trying to sell us products to make us feel we are the best, and America’s own misguided “exceptionalism,” its desire to lead the world instead of serve it, and the ways in which American advertising tries to tap into its citizens’ desires to be better than other people:

Now the presence of this instinct [to lead, to be special, to be important] explains why we are so often taken by advertisers. You know, those gentlemen of massive verbal persuasion. And they have a way of saying things to you that kind of gets you into buying. In order to be a man of distinction, you must drink this whiskey. In order to make your neighbors envious, you must drive this type of car. In order to be lovely to love you must wear this kind of lipstick or this kind of perfume. And you know, before you know it, you’re just buying that stuff.

…

[The part in italics is left out of Robinson’s take-off, but is actually what King is commenting on at the end of the Robinson’s redub] But this is why we are drifting. And we are drifting there because nations are caught up with the drum major instinct. “I must be first.” “I must be supreme.” “Our nation must rule the world.“ And I am sad to say that the nation in which we live is the supreme culprit. And I’m going to continue to say it to America , because I love this country too much to see the drift that it has taken.

Though the Colbert Show parodies the ad, making us laugh off what Dodge did with MLK, the Robinson culture jam hopes to make us aware of what MLK actually felt, and to make us feel different about consumer advertising and American exceptionalism, by hearing MLK directly address his own scorn for them, and about those who let it pander to their base desires to be better than other people. King's words are a direct criticism of the values conveyed in the ad and of advertising itself.

So it is worth considering some of the frequent differences between a parody and a culture jam, and then deciding which of the two you want to make.

Brandalism, culture jimmies® and instajams®

I take seriously Negativland's complaints about how our public space is owned and commodified by corporations. Sometimes the array of billboards and poster ads looks beautiful or interesting, but it is still being pushed on us in what should be a "commons," it seems to me.

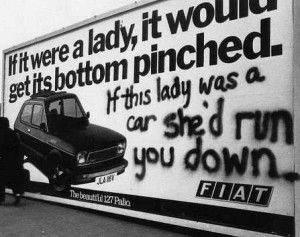

A form of détournement I would practice involves signage and other public media put out by mainstream dominant culture. As opposed to culture jamming them like subtervising or brandalism usually do, I would suggest modifying these forms of media through vandalism, to use the slick or seductive or publicly prominent platform to send more progressive or disruptive “public service messages. The idea came to me after I saw someone speak about the challenges indigenous women face.

I attended a talk in the President’s Lecture Series at Humber College in January 2017 by Dr Sarah Hunt on the special predicaments faced by indigenous women in Canada. Dr Hunt talked at length about the notorious “Highway of Tears” in British Columbia, a stretch of wilderness highway on which many native women have disappeared, in most cases later being found to have been raped and/or murdered. Spent considerable time describing the ways in which the police, local government, and the media have traditionally blamed the victims in various ways for their plight.

Dr Hunt pointed out how the B.C. government had actually put up billboards along the highway telling girls not to hitchhike, and then elaborated “So, instead of – for one – finding a bus system, this is where provicial money went, into this billboards. We don’t see billboards saying not to be violent. We instead see billboards telling girls to stay home.” This was part of her broader discussion of the various kinds of “victim blaming” going on in the response to the Highway of Tears situation.

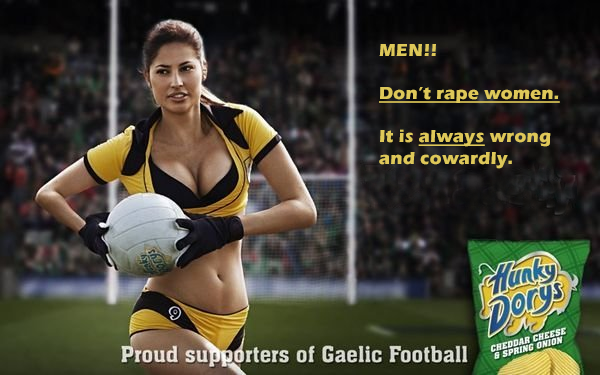

Provincial signage along the Highway of Tears

This really struck a chord with me. Why don’t we have billboards up on that highway saying “Men: don’t rape women. It is always wrong and cowardly” or something like that.

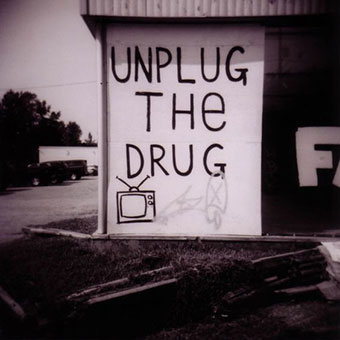

Culture jam via graffiti

Humber students can watch the video recording of Dr Hunt’s talk here.

I began to think of the ways commercial advertisers use our shared public space whether we like it or not, and how that could be “detourned.” You sometimes see this with graffiti artists who modify the messages of billboards. In those cases, it is usually obvious that the billboard has been “defaced,” but what if we could modify those signs in ways that made the modifications hard to distinguish from “official” signage?

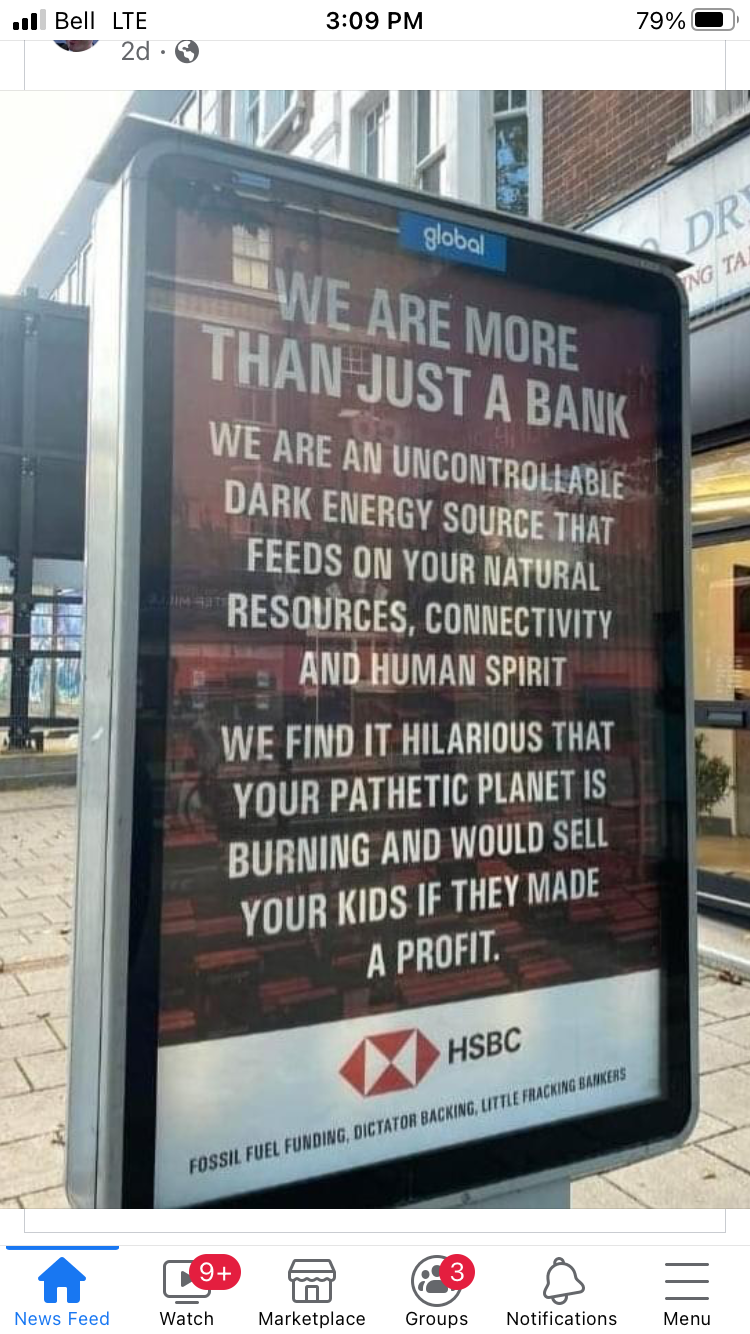

Brandalism is an anti-advertising and countercultural artists' collective (http://brandalism.ch) and also stands for a practice of recreating public signage in a sophisticated style that uses brand identities and media but subverts the messaging in a culture jamming way. These signs are actually printed and posted in ways that make them indistiguishable from mainstream advertising until you look closely at the message.

Examples of Brandalism public signage guerrila action during the 2015 Paris Climate talks.

An interesting social media activist group that seems to practice brandalism in the real world is fokawolf aka Mediacorp.

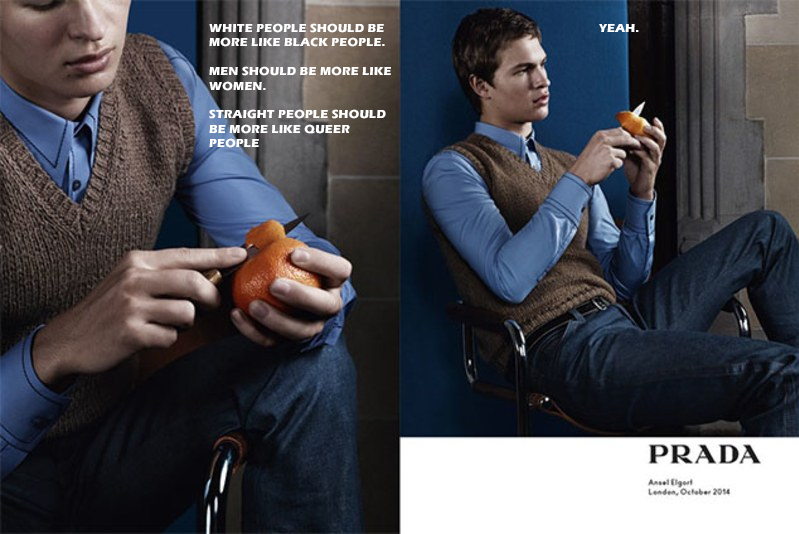

My own idea of a culture jimmy (never actually done it in the real world) is to change mainstream media that is in the public eye in a way that makes it indistinguishable from mainstream promotional media, but makes the message far different (unrelated to the brand or product, however). I imagined people creating these like graffiti artist but with slicked materials such as stencils and pasteover vinyl printing, more like some of Banky's work.

Culture jimmy of a Prada ad in the subway, which has had new text added (stencil and spray paint, vinyl lettering, etc) [concept]

Crisps ad billboard, jimmied

When I came up with the idea of a Culture Jimmy I wasn't aware of anyone actually doing it in the real world, but I have since discovered a few examples on Instagram. Most of these are in the UK. Two accounts I follow are spelllingmistakescostlives and fokawolf.

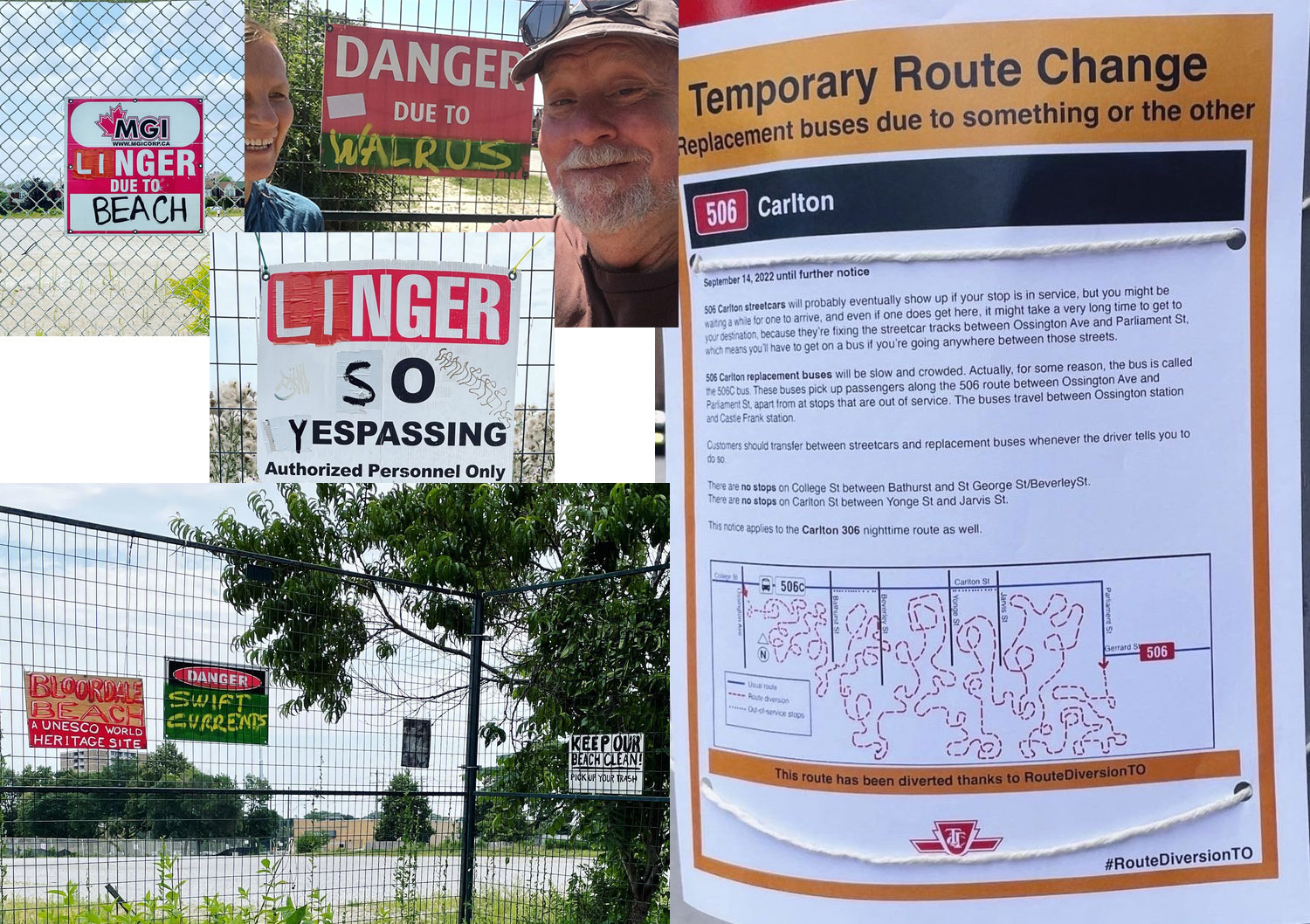

Some interesting local work has been done by Toronto-based artist Shari Kasman and her partner, aka Bloordale Beach Official. When a demolished school lot lay empty with no trespassing signs around it, they modified the signs to suggest the sandy lot was a beach. Shari even gave tours. Later when the TTC was trying to recover from the pandemic (it's still trying as of 2023), Shari made absurdist route diversion signs that were indistinguishable from official TTC signs and put them up at bus and streetcar stops.

Instajam® or Snapjam®

I define instajam as a method of guerilla détournement in which you deliver a culture jam or a culture jimmy by photoshopping it into a social media post. Also known as snapjam®.

Because it is so difficult to modify public signage in such slick ways, the practice of culture jimmy requires costly materials such as vinyl letters as well as a lot of time to “vandalize” the public media (and quite a bit of nerve). Much easier is to alter a digital image that contains signage and then post it on social media. Selfies with billboards and posters in the background are excellent candidates for this treatment.

Times Square selfie snapjam featuring culture jam in the billboard