Identity appropriation is the appropriation of a (famous) human being’s image and personality after they are dead for uses they have not agreed to. Well known examples involve the use of dead celebrities “reanimated” through digital technology and used to sell products in tv ads or as figures in fictional films.

Some ways in which identity appropriation has occurred through digital technology include

- CGI animations

(for instance, the recreation of Carrie Fisher playing Princess Leia in Star Wars: Rogue One) - Digital cut-out editing

(my favourite example: Audrey Hepburn doing a (tongue in cheek) avant-garde dance in the 1957 film Funny Face, removed and put into a different background, dancing to AC/DC to sell pants for the Gap) - Digital audio and video mashup; remixes

(for instance, a mashup of “Bittersweet Symphony” with a recorded performance of Robert Johnson from the 1930s) - Duets remixed from original masters

(e.g. Barry Manilow’s 2014 album My Dream Duets, in which Manilow intrudes on recordings previously made by deceased singers Whitney Houston, John Denver, Louis Armstrong, and others) - Sampling

(thousands of examples; e.g. Kanye’s use of Ray Charles’s “I got a woman” in “Gold Digger”) - Deepfakes

Identity appropriation is related to, and often relies on, performance abduction.

2Pac 2.0

Tupac Shakur was perhaps the most famous of all the gangsta rappers of the 1990s (apart from Biggie ,-).

He was murdered in a drive-by shooting in 1996, having enjoyed a meteoric but decidedly short career. In many of his songs he rapped about the early violent death he expected and was ready for. His lyrics are also full of Christian imagery involving ressurrection, and many projects (albums, documentaries, tributes) since his death take inspiration from the idea of his rebirth. (There was also a craze of speculation at one point that he is really still alive.)

Posthumous albums abound, and like Michael Jackson, Tupac remains one of the highest-grossing musicians out there, even though he is dead. He is reborn in documentaries, remixes and mashups, newly discovered unreleased albums, fan art, and the poorly received 2017 biopic All Eyez on Me.

But certainly the most spectacular example of Tupac’s posthumous existence was the “ressurrection” of the rapper as a “hologram” at the 2012 Coachella music festival. Using not hologram technology but in fact a technique that is over 100 years old, known as “Pepper’s Ghost,” a seemingly three-dimensional version of the dead performer shimmered on the stage and even rapped in tandem with his (still more or less living) former crew-mate, Snoop Dogg (now Snoop Lion).

The illusion is technically stunning:

But for me this event raises soul-shaking questions. In the song “All Eyez on Me,” Shakur had chanted “Live the life of a thug until the day I die / Live the life of a boss playa.” And Tupac did just as he said. But what about after the day he dies …? There is talk of taking the Tupac hologram on the road for a world tour, as has already happened with the Michael Jackson “hologram.”

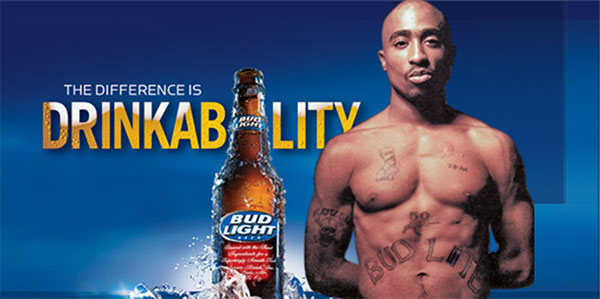

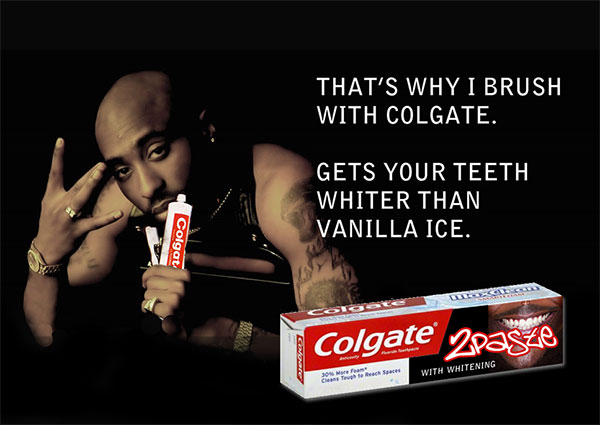

Would Tupac have gone on this tour if he had lived? Would he still be doing duets with Snoop if he were alive in 2013? Who owns the Tupac hologram? (Dr Dre put up the money to develop the stunt and Tupac’s mother gave her permission – is this really satisfactory from a legal perspective, though?) Who owns Tupac’s identity after he is dead? If Dr Dre finds himself broke and sells the hologram to Budweiser or Colgate Palmolive one day, will we suddenly find ads like these?

Maybe I’ll even be able to buy my own home version of the hologram. Tupac, can you please sing me that new Katy Perry song? Laughter all around.

As our identities become more virtual, and our virtual realities become more real, what happens to the realness of identity? In the future, who will control your identity. If you become famous, will there be a home version of you sitting on the couch as a holographic projection or a life-size robot? Will you appear in commercials for products you might have despised in real-life, as has happened with countless dead celebrities?

Digital technology allows people to “recreate” human beings (images, voices) or abduct them from a recorded context (like Audrey Hepburn’s dance in a 1957 movie) and put their performance into a new context. To the extent that a person’s identity exists through electronic media and recordings, that identity can now be edited, repurposed, added to, even if the person is no longer alive.

Deep Fakes are made by software that allows face-swapping and body swapping to create videos that appear to show someone doing or saying something that someone else actually did or said. Deepfake technology uses Artificial Intelligence to combine two video sources. 95% of existing deepfakes put a famous person’s head on a porn actor. So you could watch Audrey Hepburn do porn, for instance. Now the technology is being used on YouTube for humorous parodies such as Above the Line:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lzRt3FrFuWA

On YouTube you can find lots of funny videos – Elon Musk as a baby, etc – presented as mere comic entertainment. The legalities around this kind of identity appropriation are unclear and these “remixes” – like most of the appropriation that currently goes online – are largely tolerated. These celebrities in the video above are still alive, so at least they have some recourse if they are not happy with being face-swapped. Dead people, however, should arguably be left to rest in peace. Their identities have been finalized, and whatever truly made them them is gone.

People are growing concerned about deep fakes because of the political potential of “weaponizing” them – spreading fake videos of presidents and prime ministers, or candidates, saying and doing things they’ve never said or did, etc. But the place deep fakes began – porn – already should have been raising huge alarm bells. Take a look at what Mitali Thakor says in this TedX talk (I’ve sent you to near the end of the video, but the whole thing is worth watching.)

Much of the general public has come to see all media as entertainment and to therefore want to shrug off this brand of “identity theft” as meaningless fun. There may also be a tendency to see celebrities as “asking for it” by being famous. If they want to be famous, they should expect to be misappropriated. To concentrate on the freedom the consumer has to imagine they’re watching a celebrity crush have sex, as Thakor says, is to ignore the human rights violations of the people whose images are being appropriated for your pleasure.

And remember – as Thakor points out – it isn’t only celebrities who are vulnerable to deep fakery. If you have shared enough images of yourself via social media, you may be face swapped onto a porn star yourself. Additionally, as she also acknowledges, the porn actors are being appropriated against their will as well. Is this freedom, or a new form of virtual enslavement?

Among the technologies currently being perfected is a kind of couples’ “deep fakes” platform called DaF Masking (DaF stands for Dreams and Fantasies). So you and your partner could put on VR helmets, get into a sex act, and be seeing your partner as one of the Kardashians or Idris Elba or whoever. Or for that matter, your best friend’s partner. You could even pretend to be having sex with a deep fake of yourself!

All of these technologies call into question whether there is a difference between human identity and media images of a person, which can be simulated. Some would say that the integrity of human identity, to the extent that it is created by others’ perceptions of us, is thus in danger of being undermined. And that may include you. Imagine you are 90 years old, and pass away. Your bereaved family orders a holographic recreation of you, so that they can still keep you around. You are gone, but you continue to grow and change – as a virtual recreation. Is this a form of appropriation that needs more individual and perhaps legislative attention?