WEEK 06: Performance abduction® and identity appropriation®

QUICK REVIEW

Just memorizing the words in this box is not the same as understanding the material well enough to use it in the world, or to do well when you are tested on it. Some of this material is explained in depth starting at the left of this box, or on the main study site.

- Performance abduction®

The use of someone's recorded performance as part of your own performance or recording, without the original artist's permission. The example I concentrate on in the lesson is Kanye's abduction of Ray Charles's recorded performance of "I got a woman" in "Gold Digger," though perhaps it is not ideal, since we don't really know if West may have discussed the song with Charles before he passed away. Charles died in 2004; "Gold Digger" was released in 2005. - Identity appropriation®

The use of a human being’s image and personality after they are dead for creations they have not agreed to. Well known examples involve the use of dead celebrities “reanimated” through digital technology and used to sell products in tv ads or as figures in fictional films. - Deep Fakes

A technology that allows faces to be swapped onto different bodies creating realistic video images of people doing and saying things they never actually said or did. The original and main use in in pornography, but the technology is being applied in new ways all the time. - Postmodern decontextualization

The use of someone's creative work, recorded performance, or identity is a way that ignores or doesn't know its meaning in its original context. This occurs both in terms of appropriators who don't care about or know the context of stuff they are appropriating and also audiences who don't recognize or understand what is appropriated and what the original context was.

In the previous two lesson and this lesson, I've been focusing on three basic themes, as we looked at the evolution of American pop music in the last hundred years or so..

The first is the question of “human rights” aspects and human/social impacts of creative appropriation. These include the cultural appropriation questions, but also, especially in this lesson, the impact on personal as well as cultural identity.

The second theme is about how the rapid technological changes of the recent past have impacted what it means to appropriate, and how appropriation can be done.

The third thing I've been trying to draw attention to involves how music has gone from being a live, often participatory form of culture, to the ways the 20th century's capitalist way of treating culture as property and commodities has anti-participatory, deadening, and anti-creative aspects. Another issue is the way recording has made a music into a private and isolating experience for many people.

Performance abduction®

Performance Abduction [more properly, but awkwardly, recorded performance abduction] is my term for the unprecedented possibility of using the electronic reproduction (recording) of someone else’s performance as part of your own performance or recording. This was brought about by the rise of audio and video recording in the 20th century. Prior to recording, you could appropriate someone else's idea or tune or performing style, but you couldn't incorporate the record of their performance in your own work.

I feel this is a form of creative appropriation that has not just legal and financial, but arguably also human ramifications. To the extent that the original recording reproduces faithfully another human being’s performance in the world, it can allow appropriators effectively to make that performer (seem to) perform along with them, in work that might in no way be consistent with the reality or values of the original creator.

As I said, earlier modes of appropriation were either conceptual (taking someone’s idea, tune, plot, etc), literal (re-using someone’s words), or concrete (taking physical objects – usually mass produced – and using them as part of your own object [e.g. collage and photomontage as practised by the Dadaists, or “readymades”]).

With audio and video recording technologies in the 20th century, however, it becomes possible to use recordings of someone else’s physical (and emotional) performance (their voice, their playing of an instrument, their acting or non-acting on camera, etc) as part of one’s own creation. This seems particularly questionable to me if the appropriated artist is dead or otherwise unable to give their permission.

I think the first place something like this happens in a popular context is hip hop, in which DJs created new music by repeating, cutting, or altering musical passages from other people’s records and mixing pieces of more than one record together. With the advent of sampling and digital editing in the 1980s it becomes much easier and more common to do this kind of appropriation. Sampling is now a major component in much popular music. Unauthorized remixes and mashups abound. Ads repurpose dead performers' words and images. In the early 21st century personal computers, digitized media, and digital editing software have made it comparatively effortless for all of us to practice performance abduction. Professional commercial media producers also use it widely in music production, advertising, film making and so forth.

My concern is with the rights of the original creator/performer – especially if they are dead or don’t own the rights to their performance – and the loss or indeed ignorance of what they cared about in the repurposing of remixers who use these people’s personal performances for their own ends.

For instance, Ray Charles has no say in whether or not he sings his song about having a good woman in accompaniment to Kanye West’s bitter song “Gold Digger” about women who only want his money. That is probably an example of performance abduction in my sense. Although Charles met with Jamie Foxx to give him guidance on playing him in the 2005 biopic Ray, and Kanye seems to intend "Gold Digger" as a tie-in with that movie, Ray Charles died in 2004 and probably had no knowledge of what West ended up doing with his tune in his 2005 track.

The example of the Ray Charles song allows one to compare pre-technological appropriation and post-technological appropriation. The story of the origins of the Ray Charles song goes something like this:

The song builds on "It Must Be Jesus" by the Southern Tones, which Ray Charles was listening to on the radio while on the road with his band in the summer of 1954, as well as a bridge inspired by Big Bill Broonzy's "Living on Easy Street". He and a member of his band, trumpeter Renald Richard, penned a song that was built along a gospel-frenetic pace with secular lyrics and a jazz-inspired rhythm and blues (R&B) background. The song would be one of the prototypes for what later became termed as "soul music" after Charles released "What'd I Say" nearly five years later. (Wikipedia)

You can certainly hear the Ray Charles song elements, including a number of common blues changes in the gospel song:

On the other hand, the Southern Tones's song is itself modelled on very conventional blues progressions that were shared around quite freely in the "jes' grew" blues tradition.

This is pre-technological appropriation. Charles and Richard borrow the tune and some of the feel of the gospel song and then write their own lyrics, which have a more romantic theme. (The crossover between Christian and romantic songs was very common in the blues, and we see an ironic reversal in Christian Rock, where many of the songs about Jesus sound almost like romantic love songs repurposed.)

Kanye's hit "Gold Digger" features Jamie Foxx singing in the persona of Ray Charles and then a considerable amount of sampling of the original Ray Charles track as background for Ye's cynical rapping about women who are only out for his money:

As mentioned, the track features Foxx and was presumably intended to be a tie-in with the release of the biopic Ray (2005) in which Foxx plays Ray Charles. As I understand it, Kanye's original idea was to have a woman rap and sing the song; presumably the background sample where Ray Charles is singing about having a good woman would have felt in sad contrast with the realities of women as Kanye sees them. When that part of the project didn't come about, Kanye created the song himself, rapping about a world where women only want your money and pre-nups are de rigeuer, even if he never comes out and says that the unnamed women is a gold digger exactly. Meanwhile, in the background Ray Charles is still spilling his heart about the good woman who looks after him (a comparatively rare blues song in which a woman is not the cause of all one's woes).

I suggested in class that the use of Ray Charles singing his song could be considered disrespectful and decontextualizing, and asked if people thought it was fine to sing whatever you want over someone else's recorded sentiments as long as you've paid for the sample release.

Identity appropriation®

Identity appropriation is the appropriation of a (generally famous) human being’s image and personality after they are dead for uses they have not agreed to. Well known examples involve the use of dead celebrities “reanimated” through digital technology and used to sell products in tv ads or as figures in fictional films.

Some ways in which identity appropriation has occurred through digital technology include

- CGI animations

(for instance, the recreation of Carrie Fisher playing Princess Leia in Star Wars: Rogue One) - Digital cut-out editing

(my favourite example: Audrey Hepburn doing a (tongue in cheek) avant-garde dance in the 1957 film Funny Face, removed and put into a different background (see below) - Digital audio and video mashup; remixes

(for instance, a mashup of “Bittersweet Symphony” with a recorded performance of Robert Johnson from the 1930s) - Duets remixed from original masters

(e.g. Barry Manilow’s 2014 album My Dream Duets, in which Manilow intrudes on recordings previously made by deceased singers Whitney Houston, John Denver, Louis Armstrong, and others) - Sampling

(thousands of examples; e.g. Kanye’s use of Ray Charles’s “I got a woman” in “Gold Digger”) - Deepfakes

Identity appropriation is related to, and often relies on, performance abduction, as discussed in the previous section.

Here is the example of Audrey Hepburn, cut out of a 1954 movie and digitally manipulated to dance to AC/DC in a gap ad:

The dancing figure of Hepburn has been brilliant lifted using digital technology from the 1957 musical Funny Face:

The context of the dance in the original is quite different from how it was used in the Gap ad, obviously. The dance is performed by Hepburn partly to show her sexist date that women don't need a partner to dance anymore, and the dance itself is kind of a pastiche of avant-garde modern dance styles at the time, and what a typical American might have thought typical of the wild and beatnik entertainment that goes on in places like Paris (where this scene supposedly occurs in the movie). Hepburn's identity and her performance as that character in the film are thus decontextualized for the use of her charismatic image to sell jeans.

2Pac 2.0

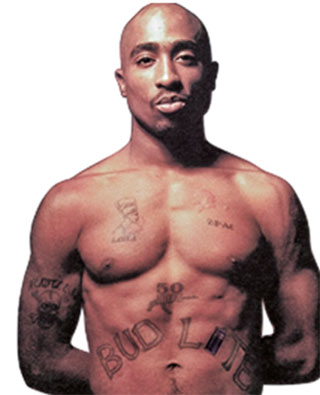

Tupac Shakur was perhaps the most famous of all the gangsta rappers of the 1990s (apart from Biggie, that is, but hey I'm from Cali. ,-).

He was murdered in a drive-by shooting in 1996, having enjoyed a meteoric but decidedly short career. In many of his songs he rapped about the early violent death he expected and was ready for. His lyrics are also full of Christian imagery involving ressurrection, and many projects (albums, documentaries, tributes) since his death take inspiration from the idea of his rebirth. (There was also a craze of speculation at one point that he is really still alive.)

Posthumous albums abound, and like Michael Jackson, Tupac remains one of the highest-grossing musicians out there, even though he is dead. He is reborn in documentaries, remixes and mashups, newly discovered unreleased albums, fan art, and the poorly received 2017 biopic All Eyez on Me.

But certainly the most spectacular example of Tupac’s posthumous existence was the “ressurrection” of the rapper as a “hologram” at the 2012 Coachella music festival. Using not hologram technology but in fact a technique that is over 100 years old, known as “Pepper’s Ghost,” a seemingly three-dimensional version of the dead performer shimmered on the stage and even rapped in tandem with his (still more or less living) former crew-mate, Snoop Dogg (now Snoop Lion).

The illusion is technically stunning:

But for me this event raises soul-shaking questions. In the song “All Eyez on Me,” Shakur had chanted “Live the life of a thug until the day I die / Live the life of a boss playa.” And Tupac did just as he said. But what about after the day he dies …? There was talk of taking the Tupac hologram on the road for a world tour, as eventually happened with the Michael Jackson “hologram.”

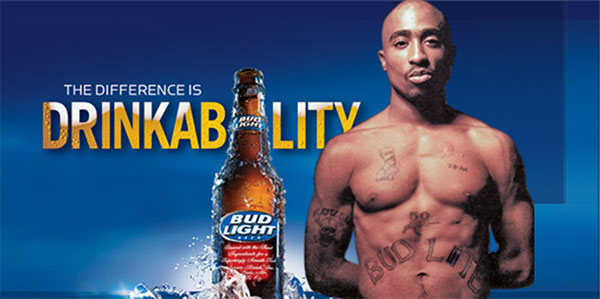

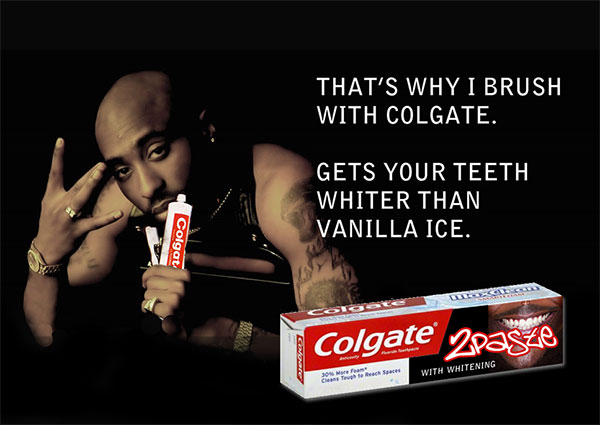

Would Tupac have gone on this tour if he had lived? Would he still be doing duets with Snoop if he were alive in 2013? Who owns the Tupac hologram? (Dr Dre put up the money to develop the stunt and Tupac’s mother gave her permission – is this really satisfactory from a legal perspective, though?) Who owns Tupac’s identity after he is dead? If Dr Dre finds himself broke and sells the hologram to Budweiser or Colgate Palmolive one day, will we suddenly find ads like these?

Maybe I’ll even be able to buy my own home version of the hologram. Tupac, can you please sing me that new Katy Perry song? Laughter all around.

A more recent, and perhaps more controversial example of reanimating the dead occured in 2021, when Kanye presented Kim Kardashian with a special birthday surprise: a "holographic" representation of her deceased father, speaking to her from beyond the grave. Or as she described it "A special surprise from heaven." Here's a bit of "Robert Kardashian's" wishes, starting at my favourite part (this will be on the test!):

It's hard to know where to begin with an analysis of this gesture. It's literally a life-like simulation of her father speaking to her. But where did the words come from that he is saying? Whose voice is actually saying them? Would her father have said these words to her, behaved in this way, if he were still alive, or if he were actually able to speak to her from heaven? Whose message is this really? "You married the most most most most most genius man in the whole world - Kanye West." Hmm. Kardashian's father's image is recreated here. But whose identity is being expressed through it? This is what I'm getting at with the idea of identity appropriation.

Deep Fakes

Technology that allows someone's image to be appropriated is progressing by leaps and bounds. Deep Fakes are made by software that allows face-swapping and body swapping to create videos that appear to show someone doing or saying something that someone else actually did or said. Deepfake technology uses Artificial Intelligence to combine two video sources. 95% of existing deepfakes put a famous person’s head on a porn actor. So you could watch Audrey Hepburn do porn, for instance. Now the technology is being used on YouTube for humorous parodies, but could presumably become common in advertising, movies, and for dangerous political uses.

As the Belgian developer says in the news feature, people have become worried about the use of Deep Fakes for political propaganda, for instance making Justin Trudeau seem to say or do things in a video that he never said or did. As these technologies mature, it will presumably be harder to use video footage as evidence in a court of law (or the court of public opinion), since it could so easily be faked. The developer discusses how a lot of work is being done on finding ways to use technology to detect these fakes so that we can know when video footage is a true representation of something that happened.

As mentioned earlier, Deep Fake technology was originally developed for and still most often seen in pornographic "entertainment products." In an Ted talk from 2019, Mitali Thukor talks about how this is being treated as only relevant now that it might be used for political purposes, and how the way people are trying to combat it is by creating more technology to expose when something is a fake. But the idea of the faking people's identity itself - originally in porn - is not debated from a moral and political perspective. These "entertainment products," whether comedic or pornographic are treated as harmless fun, and the process is not apparently technically illegal in most contexts:

On YouTube and TikTok you can find lots of funny videos – Elon Musk as a baby, etc – presented as mere comic entertainment. The legalities around this kind of identity appropriation are unclear and these “remixes” – like most of the appropriation that currently goes online – are largely tolerated. Tom Cruise is still alive (unless he's just a hologram), so at least he has some recourse if he is not happy with being face-swapped. Dead people, however, should arguably be left to rest in peace. Their identities have been finalized, and whatever truly made them them is gone.

Much of the general public has come to see all media as entertainment and to therefore want to shrug off this brand of “identity theft” as meaningless fun. There may also be a tendency to see celebrities as “asking for it” by being famous. If they want to be famous, they should expect to be misappropriated. To concentrate on the freedom the consumer has to imagine they’re watching a celebrity crush have sex, as Thakor says, is to ignore the human rights violations of the people whose images are being appropriated for your pleasure.

And remember – as Thakor points out – it isn’t only celebrities who are vulnerable to deep fakery. If you have shared enough images of yourself via social media, you may be face swapped onto a porn star yourself. Additionally, as she also acknowledges, the porn actors are being appropriated against their will as well. Is this freedom, or a new form of virtual enslavement?

Among the technologies currently being perfected is a kind of couples’ “deep fakes” platform called DaF Mask (DaF stands for Dreams and Fantasies). So you and your partner could put on VR helmets, get into a sex act, and be seeing your partner as one of the Kardashians or Idris Elba or whoever. Or for that matter, maybe, your best friend’s partner, or someone you've been stalking on social media. You could even pretend to be having sex with a deep fake of yourself!

Postmodern Decontextualization

I use the phrase postmodern decontextualization to refer to the way appropriation has typically been used in consumerist manufactured culture since the 1980s or so. Decontextualization has always been a part of cultural evolution, but is happening fast and taken for granted in much of mainstream culture today.

There are two ways in which appropriated work may be decontextualized: (1) the appropriaters may be ignorant of or indifferent to the work’s meaning in its original context, and (2) the audience may be ignorant of the original context entirely.

Decontextualization and recontextualization happen when a creative statement is removed from its original political, social, and aesthetic context and put into a new one. For instance, the funky disco song “Good Times” from the 1970s was written for a mainly African American audience as a dance track, and was meant to celebrate some relaxing time off, dancing. When it is used as the soundtrack for driving around committing crimes in the video game Grand Theft Auto it has been taken from its original context and applied to a new one. There is irony in this, but only if the audience actually knows the song's original context.

The idea of postmodern decontextualization is that it is now really easy to repurpose other people’s work and performances in new contexts. Commericial appropriaters such as advertisers do this all the time. For instance, the 60s Bob Dylan protest song “The Times Are A-Changin'”was used in the 90s BMO online banking ad. The original song was anti-establishment and about social change (anti-racism, feminism, counter-culture alternatives to mainstream capitalism, etc). The assumption has evolved that appropriation is strictly a legal matter, that as long as you have paid to use something in a new context the decontextualization is perfectly fine, in fact normal.

In many cases, as with the Bob Dylan song, the original context is well known and understood by the appropriaters, and they want at least some of the original context to colour their new context for at least some members of the audience (the baby boomers who are reminded of their rebellious youth and are expected to associate those feelings with the “radical” newness of banking on the Internet). In other examples, however, appropriaters may be unaware of or indifferent to what the work meant in its original context.

For instance, in the Audrey Hepburn Gap ad the original context is unimportant to the appropriaters. Hepburn's dance was arguably a vague "feminist" statement from a character who was countercultural in the original 1957 context. The dance is recontextualized as an ad for skinny black jeans, and occurs to the accompaniment of the AC/DC song “Back in Black.” The new context is a party girl looking good in her black pants. The AC/DC song has a vaguer original context, but the lyrics sound not unlike an anticipation of rap songs where gangstas talk about getting out of prison (or free of something) and living large, for the moment. I don't think skinny black jeans would be part of the imagined new freedom - "Back in Black" is again a statement by rebels, now being used to sell jeans.

The appropriaters may have liked some of these residual resonances of rebeliousness, but they don’t need or want most of them in their performance abduction from Funny Face. More to the point, the typical viewer of the ad, especially those in the Gap’s target audience, are unlikely to recognize the context of Hepburn’s dance at all, and may not even recognize Hepburn.

The appropriaters thus don’t care about and the audience mostly knows nothing about

- The intentions of the film maker or the scriptwriter

- What the choreographer was trying to do with the dance

- Who Audrey Hepburn thought she was when doing the dance – what either Audrey Hepburn’s character or Audrey Hepburn herself was dancing for

- The intentions of AC/DC in writing “Back in Black” and how their original audience would have understood the song

Although it is as common as dirt, I’ve been trying to suggest that postmodern decontextualization can be seen as disrespectful, ignorant, and a dangerous practice when the appropriaters themselves don’t understand the contexts of the works they are appropriating. Because some people will know the original context.

There are frequently painful ironies in examples of postmodern decontextualization, for those who know and understand the original contexts. As I mentioned in the first lesson, when Puff Daddy uses a sample of “Every breath you take” by the Police, it adds an unexpected erotic (and creepy) undertone to a song that is meant simply to speak tenderly of his fallen friend, Biggie. Anyone who knew and understood Bob Dylan's “The Times Are A-Changin'” would find it offensive that the song was being used to advertise a bank.

I suggest that there are at least three good reasons, even just strategically, why appropriators should fully understand the work they are appropriating in its original contexts:

- Because this shows the respect for and understanding of the original creator that the remixer themself would probably like for their own new creative work

- Because the experience of the new work is richer and more multidimensional if the meanings, feelings, and context of the original operate as part of the new meaning and context

- Because if the audience does understand the context of the original work, but the remixer doesn’t or ignores it, the audience may get a different message or have a different experience than the remixer intended

I think the brilliant technological innovations that allow us to sample other people's work, manipulate their images, and rip things out of one context to make them take part in another one raise many serious moral, political, and existential questions. Behind them is a large question: What we can do, technologically and legally vs What we should do, for the sake of humanity.

I end the lesson, and the first half of this course with this question for you to consider: What do we appropriators today owe to the creators of the past?

- Nothing

- Royalties

- Acknowledgement

- Respect

- Knowledge, true understanding

I hope you'll continue to think about these questions as the course moves on after the midterm.

Thanks for reading.