WEEK 02: IMAGES, IRONY, HISTORY

QUICK REVIEW

Just memorizing the words in this box is not the same as understanding the material well enough to use it in the world, or to do well when you are tested on it. Some of this material is explained in depth starting at the left of this box, or on the main study site.

- Viral vs. Meme vs Image Macro For the purposes of this course, please use these terms in this way:

Viral A piece of media (often professionally produced) that gets SHARED a lot, but does not necessarily get remixed, and may until recently have been hard for the average person to appropriate and remix. (eg, Walmart yodel boy)

Meme A piece of media (often NOT professionally produced) that gets appropriated, REMIXED a lot, and used as a vehicle, motif, or “shell” for communication. (eg, Scumbag Steve)

Image Macro A specific kind of meme where an image is overlaid with text; the image is reused by many different Internet creators, but the text changes

- Meme Shells®

Jim Nielson’s term for well-recognized old images and visual clichés that have been so widely reproduced and re-used that they have lost most or all of their original meaning. Sometimes they are used as exploitables in image macros.

- Nowjacking®

A form of cultural appropriation in which historical cultural contexts are ignored in favour of suggesting that current cultural norms have always been present, or are more valid than the context of the original. - Retromania®

A shorthand term for the tendency of post-World War 2 (1950s - ) mass culture to recycle itself and ignore the majority of pre-20th century or even pre-World War 2 culture, especially the massive legacy of high culture that generally requires education to be appreciated (e.g., Renaissance art, classical music, 19th century poetry, etc).

- Irony

Saying one thing and meaning another. Read more....

Memes and Virals

I’m tentatively including memes under the modes and genres of creative appropriation because I adopt Limor Shifman’s definition of a meme in her very lucid and penetrating book, Memes in Digital Culture (2013).

The word “meme” was originally coined by Richard Dawkins in the final chapter of his book on sociobiology, The Selfish Gene (1976). This was long before the Internet became a thing ordinary people were aware of or started to use. Dawkins used the word to describe a theoretical “unit of selection” in the evolution of ideas, similar to the “gene” in the evolution of organisms.

Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation.

Today, most people use the term loosely to refer to things that are propagated through social media on the Internet. So among the many uses of the term, the following are fairly common:

- A theoretical unit of selection among human ideas, comparable to the gene in biology. (Original sense)

- Any piece of media shared through social media.

- An image or concept that is well known and has become a convention for communication & creation via social media.

- An image with text added to it. (this is more technically referred to as an IMAGE MACRO)

- An amateur video that is shared for its entertainment value or surreal impact (“dank meme”).

- A viral motif that propagates across the Internet, building or playing off on the same image or text template [broad but also the strict sense in this class]

Virals vs memes vs image macros

Shifman proposes that we use the term viral for “a single cultural unit (such as a video, photo, or joke) that propagates in many copies” – for example, the original music video of “Gangnam Style” (2012). It doesn’t change, it just gets re-posted, re-tweeted, etc.

Memes, on the other hand, are derivatives of virals that propagate across the Internet, building or playing off on the same motif – for instance, the parodies, variations, and take-offs on “Gangnam Style.” Thus, “Gangnam Style” as a meme is not the original video, but the motif or “trope” of “Gangnam Style” in its mutated life in other contexts The Gangnam Style meme is “Gangnam Style” appropriated and remixed. in other words.

As Shifman conceives of them, virals are often glossy professional creations that ordinary web citizens would find it difficult to create or remix themselves (“Taylor Swift’s latest video went viral 10 minutes after it went live” – i.e. the video was shared and mentioned by people).

Memes, on the other hand, tend to have certain features that make them easier to appropriate for people with limited technical skills or resources. They are often simple, repetitive, and easy for amateurs to remake. for instance image macros (see below).

One way of thinking about the distinction between virals and memes that Shifman suggests is that virals are items that people are motivated to share (without modification), whereas memes are items that people are motivated to engage with creatively.

One responds to virals passively, by propagating them without altering them. Memes are variant versions of a single motif, idea, image etc that various people have messed with.

People often use the word meme to denote the sort of combination of image with text that we see in this variant on “Scumbag Steve”:

Scumbag Steve “Meme” (image macro): Hey Man Can I Borrow … Everything?

There is a more technical term for referring to this particular kind of meme (a single image with a caption or text overlay of some kind): an image macro.

For the purposes of precise communication, I am encouraging you to refer to what we see above (an image with text overlay) as an image macro (that is the kind of work it is, or its genre). It is also one example – and an appropriate one given the subject of this website – of the Scumbag Steve meme. The original video of “Gangnam Style” meanwhile is not a meme, but a viral.

If we accept Shifman’s definitions, all memes are by nature a form of appropriation art or remix, but people sometimes refer to the process of adopting and detourning an existing meme, as meme hacking. Such people are taking the concept of meme in its broadest sense, and including anything in our culture as a meme (close to the original sense of Dawkins). Shifman, on the other hand, is focusing on a meme as precisely an element of culture that has been detourned or remixed.

A company logo, for instance, could be viewed as a meme; but it might be more useful to consider it a viral, or – given that it is not merely being freely shared by members of the online community but is propagated through corporate and capitalist “propaganda” techniques (which can now include social media campaigns) – a parasite or “forced viral.”

Irony

Irony occurs in a situation where one thing is stated or assumed but another thing is true.

It has become a “go to” strategy in much of Western culture for seeming hip. As a form of expression, it generally involves overstatement or understatement, or sarcasm, and the recognition by the spectator that you mean something other than what you are literally expressing. Its most basic form is sarcasm, of which Oscar Wilde called "the lowest form of wit (but the highest form of intelligence)." I think irony is frequently a defense mechanism. In my lifetime, it has indeed been used to show one's intelligence (and detachment), but now that it has trickled down into the default mode of communication for almost everyone in North America, it is no longer clear whether it still works well to signal intelligence. Many people - including me at times - have adopted a "knowing" attitude without actually knowing all that much.

Literary and culture critics often divide irony into three distinct types: situational irony, dramatic irony, and verbal irony. I would like to suggest, however, that there is a fourth type, which I call equivocal irony. I grew up in a world addicted to equivocal irony, and have often found myself using it without really thinking.

In situational irony, fate makes something undermine someone’s best efforts or assumptions, or poetic justice occurs, seemingly accidentally. Or the intention of one’s actions may be undermined due to one’s own incompetence, despite the best of intentions.

Texting while driving

Dramatic irony occurs when a reader or spectator knows something that a character in a fictional story does not know, and this makes the meaning of a situation different for the audience than it is for the character. (This can also occur in real life, when some people know something that another one doesn’t, leading the ignorant one not to correctly or fully understand the implications of something.) For instance, at the end of Romeo and Juliet, Juliet drinks a potion that makes her appear to be dead. This is so she doesn’t have to marry another suitor and can hopefully still get together with Romeo. Romeo discovers her and believes that she actually is dead (though we know she isn’t). He is so distraught, that he commits suicide to be together with her in death. She awakes and finds Romeo dead and then decides actually to kill herself.

Verbal irony is similar to sarcasm, or a use of overstatement or understatement that is meant to be understood by your audience and change the emotional meaning of what you are saying. With verbal irony, you say something, but you don’t mean it, or mean it in a different sense. Often you are saying exactly the opposite. For instance, the famous opening line of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” This is meant to be ironic and funny, because it is not in fact a universal truth at all, and indeed the opposite would be more likely or more sensible. What does a rich man need with a wife?

Much literary satire relies on the reader understanding that the narrator does not mean what they are literally saying. In a famous satire, A Modest Proposal, Jonathan Swift carried on an extended bout of such irony. The pamphlet was written to address a severe famine in Ireland and Swift tries to create outrage and action in his reader by proposing, in a deadpan way, that the starving Irish children be repurposed as food for the English, thus cutting down on the population of impoverished Irish people. This is done “with a straight face” but it is assumed that the audience knows he is actually trying to draw attention to the hard-heartedness of the English, so they will do something to relieve the Irish in this time of need. For instance, “I rather recommend buying the children alive and dressing them hot from the knife, as we do roasting pigs.” By exaggerating his apparent cruelty to the Irish, Swift hoped to make readers recognize their own callousness in not doing something to help in the relief of them.

Verbal irony typically uses overstatement or understatement for its effects, and may also make use of plays on words. Hamlet’s words to his mother “It is common” seem to agree with and confirm what she is saying to him, but if we are paying attention we recognize that he is actually criticizing her attitudes as unfitting for a member of the nobility> “It is common” seems to agree with his mother’s claim that her behaviour is normal, but here Hamlet uses irony to also mean, “yeah, your behaviour is low-class and typical of a not very educated or noble individual, a commoner.”

If verbal irony is often defined as “saying one thing and meaning another,” equivocal irony is a form where one could be said to be “saying two things and meaning nothing.” It is very common in our culture, and frequently used in parody, which often both criticizes and reaffirms values and situations.

Ambivalence is a common and understandable attitude to have toward much of our culture. One may enjoy looking at beautiful thin women, want to be a beautiful thin model oneself, and still deeply regret that our culture is so focused on beautiful thin models. One may enjoy that fact that Donald Trump’s presidency is a source of humour and entertainment and at the same time feel that it is terribly sad and dangerous to have him as president and to have a mass media so ready to use the situation for entertainment and clickbait.

The ambivalence is understandable, but it can argued that it is a conservative force. Making such ambivalence the “message” of one’s creative work is not really productive of anything. It reinforces the current situation, with its mix of positive and negative feelings. It leaves the negative part in place and the ambivalence unresolved. Like so much of parody, it re-normalizes things that arguably should be made to look creepier and less acceptable, so that the world moves in a better direction. Equivocal irony leaves things where they are, and has come to seem a very weak and pointless gesture in the world. Many parodies, culture jams, and other forms that think the world is bad nevertheless take a kind of “bitter irony” attitude toward the badness: this is bad, but it’s inevitable and can’t be changed. Irony is a coping mechanism in an unacceptable world, but as a tool for change it is not always foolproof. Sometimes it encourages the audience to accept the badness with a resigned sigh or a bitter chuckle, rather than rise up and demand change.

Equivocal irony is a second-order irony that more or less corresponds to what YouTube political satirist JrEg calls “meta-irony.” In a very instructive video, JrEg distinguishes between “post-irony,” which is more or less an additional layer of irony to reassure one’s audience that the creator knows irony is a necessary component in communication among intelligent people now, and “meta-irony” which is a defense mechanism suggesting that one doesn’t know what to say or what one thinks.

JrEg has devoted more than one video to discussing the difficulty of expressing something sincerely or getting a point across in a culture addicted to irony. Here he skewers practitioners of “meta-irony” as confused, ignorant, or simply afraid:

With meta-irony it’s almost as if the author themselves is in a state of confusion over what they’re trying to say because of this meta irony.

Meta irony is really, like, pointless.

By employing meta-irony here you’re basically saying, “Look at this thing – it exists,” but that’s really all you’re saying. You’re not saying anything about that thing except that it is something you can point to.

I think a lot of the time meta-irony comes from a place of genuine confusion and post irony comes from a place of trying to hide an opinion with a layer of irony, but of course these are literary devices; there’s no connotation associated with them, and they can be used in any number of ways. This is just how our generation tends to use them on the Internet.

Creative people often think that what makes something art is that it leaves interpretation open to the viewer and perhaps strives to present opposing elements and values in an unresolved equilibrium. This is really only one idea of art, however. It became widespread in Western culture during the Modernist period of the early 20th century and became almost doctrinaire in the postmodernist climate of the second half of that century.

Creative people often think that what makes something art is that it leaves interpretation open to the viewer and perhaps strives to present opposing elements and values in an unresolved equilibrium. This is really only one idea of art, however. It became widespread in Western culture during the Modernist period of the early 20th century and became almost doctrinaire in the postmodernist climate of the second half of that century. Dimestore irony gradually became not a radical disruptive force, but the new normal in books, television, and movies. One of the problems with irony is that expresses our ambivalence and uncertainty about the status quo, rather than a better alternative. But that is only one kind of art, and one kind of attitude toward reality. To me it seems increasingly to be a weak and lazy way of copping out. Art doesn’t have to always be about indifference. Perhaps that kind of art is a luxury of those with few serious real problems and a lot of leisure time. If so, then such people commenting on serious or political matters with an attitude of equivocal irony are reproducing a wrong world and tacitly saying they don’t care. Such equivocal irony is partly useful because it helps us not care. In that, it seems more like an anaesthetic than an aesthetic.

Art and imagination can change the world. Equivocal irony, ambiguity, ambivalence leave the world in a holding pattern.

Most creative irony relies heavily on your audience already sharing your worldview. Ironic statements are thus “preaching to the choir” and unlikely to change anyone’s mind. You have actually said something you don’t really mean, and this can even be used by those who aren’t on your side to support their own views or the relativity (and therefore ignorability) of all positions.

In a social and cultural world that is increasingly diverse, it is harder and harder to be sure that members of your audience will share your understanding of reality and thus be able to appreciate your irony as irony. On the whole, I believe the technique is overused in our own mainstream culture today, and also overused by those who want to challenge or change that culture.

Use irony wisely and sparingly.

Irony: Do not let yourself be governed by it, especially not in uncreative moments. In creative moments try to make use of it as one more means of grasping life. Cleanly used, it too is clean, and one need not be ashamed of it; and if you feel you are getting too familiar with it, if you fear this growing intimacy with it, then turn to great and serious objects, before which it becomes small and helpless. Seek the depth of things: thither irony never descends – and when you come close to the edge of greatness, test out at the same time whether this ironic attitude springs from a necessity of your nature. For under the influence of serious things either it will fall from you (if it is something fortuitous), or else it will (if it really innately belongs to you) strengthen into a stern instrument and take its place in the series of tools with which you will have to shape your art.

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet (Letter of April 5, 1903)

Don't try this at home - at least not for your creative project in this class

Certain kinds of "remix" that are otherwise legitimate are not really suitable given the precise challenge you are being encouraged to explore in this class. There are also many things that bug me personally and that I have seen too much of, so I am going to draw them to your attention and ask you to avoid them, for the purposes of this class and the Creative Project. A lot of these have to do with misleading use of historical media.

Nowjacking®

A form of cultural appropriation in which historical cultural contexts are ignored in favour of suggesting that current cultural norms have always been present, or are more valid than the context of the original.

This is a form of anachronism and decontextualization, and at times it could even be viewed as recuperative since it could remove any oppositional potential still to be found in historically remote works in order to bring them in line with mainstream values and ideas today, and suggest that those attitudes are eternal and natural.

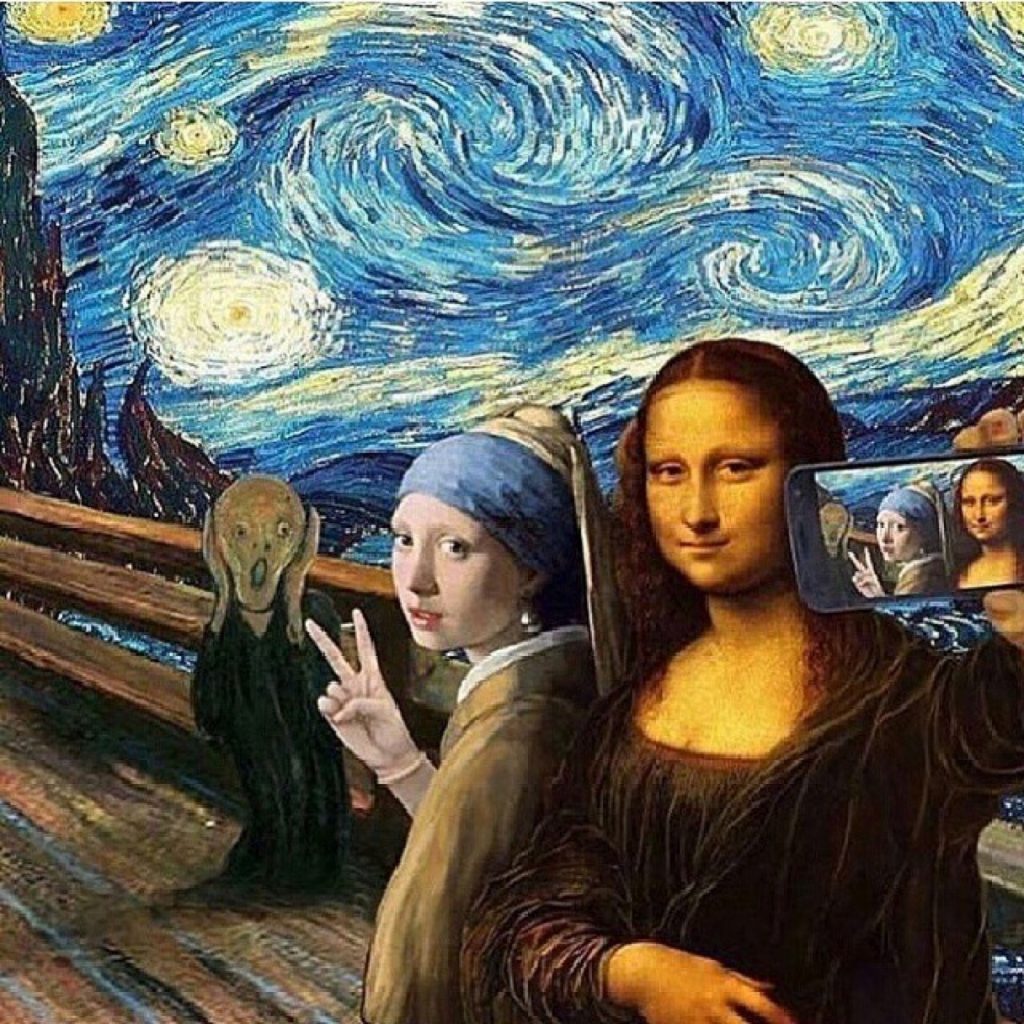

Consider the beautifully rendered mashups of famous Western art masterpieces by Olivia Muus, “Museum of Selfies” from 2016.

Olivia Muus, Mona Lisa and The Girl with the Pearl Earring Selfie (2016)

These digital montages are superbly done, and it could be argued that they might work to interest people in classic art by suggesting that the figures in them are as interesting as the subjects of selfies in one’s feeds. But they also have the effect of insinuating that the subjects of these paintings were just like us, and took part in their own version of the pervasive spectacle of narcissism and self-publicizing that is so prevalent in the selfie-lebrity media of today. That “selfie” attitude toward the self – as an object for self-promotion through the mass media – was obviously not present in most (perhaps any) of the original subjects of the paintings repurposed by Muus.

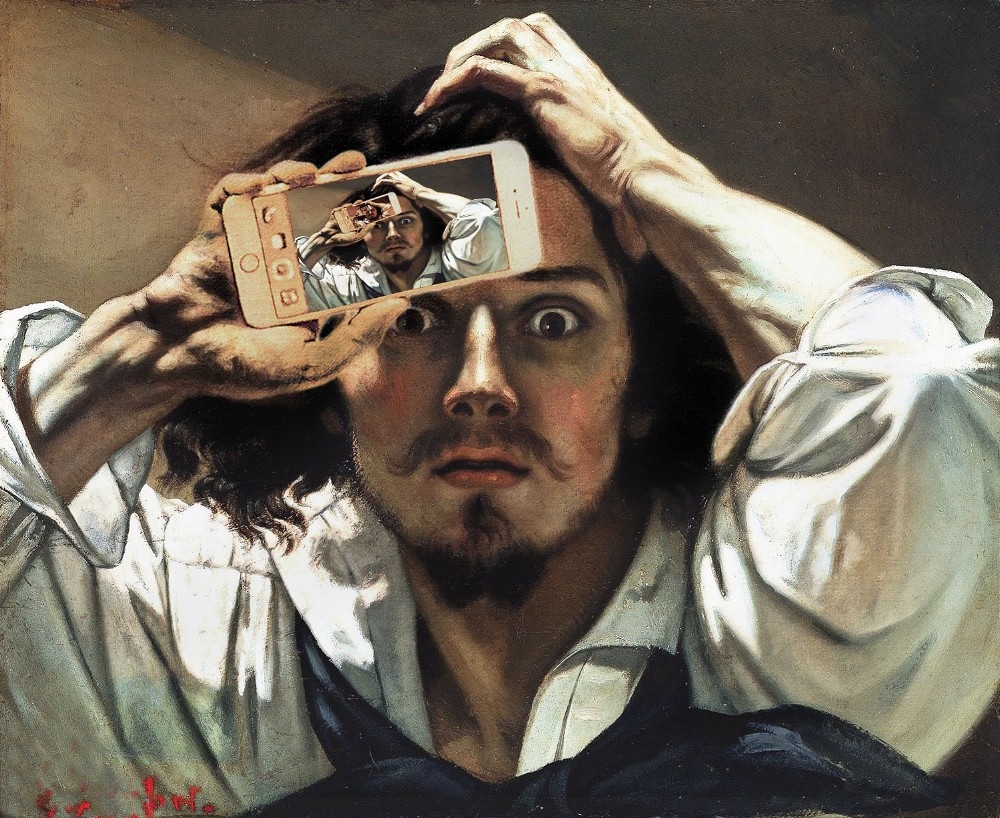

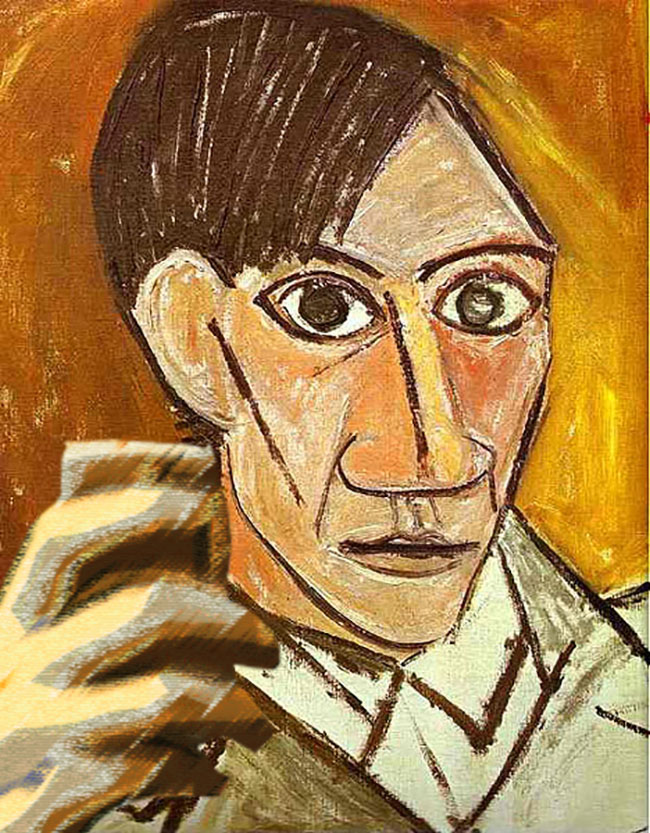

Some of Muus’s selfie edits are really fantastic looking. But only two of them were anything like a “selfie” originally, the artist Gustave Courbet’s The Desperate Man (1843–45), a self portrait of the artist, and Picasso’s 1907 self-portrait.

Olivia Muus, Man taking a Selfie in a Courbet Painting (2016)

Olivia Muus, Picaso Selfie (2016)

Muus’s title for the Courbet remix, “Man taking a selfie in a Courbet painting” makes one wonder if she was even aware that “The Desperate Man” was a self-portrait.

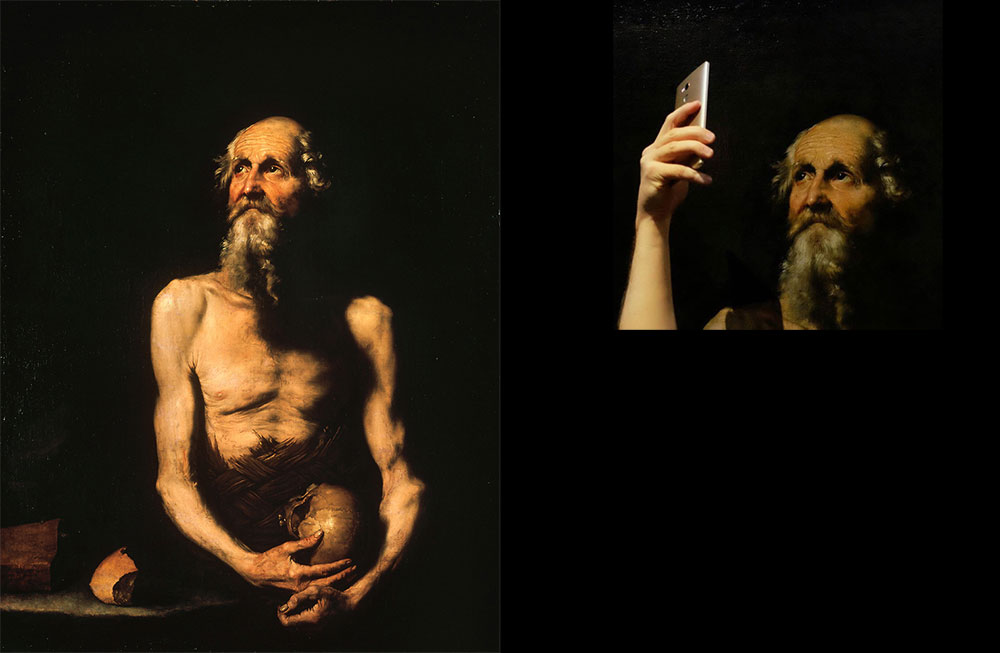

Other paintings in her series present subjects taking selfies that could hardly be further removed from our world of narcissistic self-promotion. Consider, for instance, her take on Jusepe de Ribera’s St. Paul the Hermit (1647).

L. Jusepe de Ribera, St. Paulus Eremita (1647) x R. Olivia Muus, Selfie Paulus Eremita 1647 (2016)

de Ribera’s painting represents St. Paul living alone in the wilderness, far removed from the rest of humanity. He holds a human skull in his hand. Such a skull was known as a memento mori (“remember that you will die”), and was a common motif in Renaissance art. The skull is meant to humble a human being, reminding them that this world and its honours are transient. Living as a hermit was a way people avoided the distractions of society and anxiety about things like status in order to get in touch with themselves and God. Muus’s replacement of the skull with a cellphone could be considered bitterly witty, assuming she was aware of all this; but unless a viewer is fairly well-educated and has some historical savvy they will more likely just think the image suggests that anyone appearing in a classical painting was as hungry for celebrity as our current selfie-lebrities are.

Such images are thus de-historicizing and, because they are so often made by people who know little to nothing about the original contexts of the art works, typically decontextualizing. They give a false sense of historical continuity and reassert the "normalcy" of our own attitudes toward the world today. In fact, our own attitudes toward the world, ourselves, each other, and what matters may be as weird, and will almost certainly be as short-lived, as all of the other ideologies that have seemed natural and eternal to human beings.

Historians and cultural critics sometimes refer to this anachronistic introduction of present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past as presentism. Presentism is another form of cultural chauvinism, the uncritical adherence to present-day attitudes, especially the tendency to interpret past events in terms of modern values and concepts. It is simply not true, for instance, to say “we have always been capitalists.”

The action of nowjacking usually differs from détournement – which also aims to repurpose old works to make them express new messages – in that détournement is trying to critique and change our current culture and society, while nowjacking tends to re-affirm its legitimacy and suggest that it has always been like this.

Meme shells®

This is my term for well-recognized old images and visual clichés that have been so widely reproduced and re-used that they have lost most of their original meaning. Such images are empty of significance for most viewers, or at most carry a tiny bit of connotation of some sort. People who have seen them reproduced but do not know anything more about them seem to find them so empty they can now operate as exploitable images for memes.

Exploitables are usually pictures of anonymous people or animals that have no clear, obvious, or known context. Meme shells are images that actually have (at least historically, and still for some people) a lot of context. However, the images have been so widely seen in popular culture (and now in memes themselves) that some people now feel comfortable using them as (empty) shells for memetic messages.

A classic example of a meme shell is the Mona Lisa. Almost everyone has seen it many times, but like so many images in celebrity pop culture, it may mean little to them except that it is famous. It’s become another empty, decontextualized image.

There is a fair bit of history behind this painting, however, and people who love it or have studied it see it as a painting rich in contextual meanings. It means little to the typical uneducated viewer today, on the other hand, except that it connotes fine art, high art, or a great painting. Few people know anything about its history, and most people have seen it reproduced so many times that they do not respond to the “seductive” or “enigmatic” smile that used to get people excited. Instead, it is just a familiar, but arguably dead (meaningless) image.

A lot of famous paintings from the Western tradition with Christian themes fall into this category. Even people who call themselves Christians today may know or feel relatively little about the scenes depicted in them, for example da Vinci’s Last Supper, or Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper

Like da Vinci’s Last Supper, Mount Rushmore, the silly monument to four American presidents carved into the mountains in South Dakota, has become a convenient shell for putting a bunch of celebrities together in a “work of art”:

The meaning of The Last Supper is usually completely irrelevant to the remix of it and although Mt Rushmore sometimes brings a bit more meaning with it, as it can be used to revise the concept of “American Greatness,” it is often just a framework to hold someone’s favourite heroes, some people one finds laughable, or some meme figures.

All of the images above have been parodied and used as examples thousands of times, so even the least educated people may well recognize them. But for most people, the images themselves are meaningless. The Last Supper has been repurposed for many Internet memes that do little except group a sub-set of celebrities at the table. The original Biblical meaning and iconography contributes little or nothing to these memes.

The Mona Lisa is probably the most remixed image from the Western tradition of art. It has been so overused that it has virtually none of its original meaning – and no meaning at all, apart from a vague connotation of art and an idea of a beautiful woman – for the average viewer. Representing Kim Kardashian as the Mona Lisa in particular is not an original or interesting idea. Do something more creative and worth saying.

Mona Kardashian has been done to death.

Other paintings of this kind that are often appropriated mainly for their familiarity by people who don’t know or care anything about their original meanings or content include Van Gogh’s self portraits, Warhol’s Marilyns, Dali’s The Persistence of Memory, van Eyck’s Arnolfini portrait, and many other paintings that have attained meme status but about which most people know next to nothing.

Munch’s The Scream may be a special case – partly because it is so negative and does express anxiety and horror even if the viewer knows nothing more about it. Grant Wood’s American Gothic when it gets memed is often used to represent “what really typifies Americans.” On the subject of Americans, it might be added that images like the Uncle Sam poster and “We can do it” are also falling into this category of empty, exploitable shells. All of these images are so overused as to be almost played out of any real meaning.

Tired “Amemicana” shells

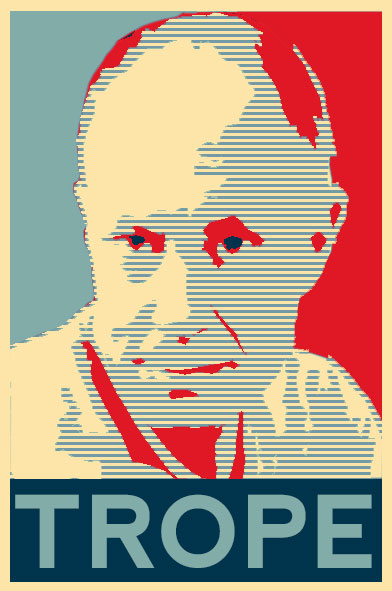

Shepard Fairey’s HOPE poster has been so widely appropriated, parodied, and memed that the style itself is now a sort of meme shell, and there are online generators and app filters that will take your image and turn it into a poster in that style without much effort on your part. Although something radical could probably still be done with the Fairey original of Obama, most people use it with little understanding of the original context, and using the HOPE format is rarely a really creative (transformative) mode of appropriation.

Fairey HOPE poster with a few of the dozens (hundreds?) of knock-off memes based on it

The word trope is a term from literary and rhetorical analysis, referring to a word or expression used in a figurative sense. For instance, if somebody says “she’s doing a tightrope walk with her grades this term” they do not literally mean that she has her grades with her as she walks across a tightrope. “Trope” has gradually come to be used by literary theorists to refer to common and much reused metaphors – referring to love or desire as “fire,” for instance – and has gradually trickled down into common usage where it tends to be used to refer to a tired cliché. (“The trope of the robot who is more human than the people who built him is familiar from many works of SF.”)

Effective figurative words and images tend to move from being true tropes (original, striking metaphors) to becoming commonplaces (familiar tropes) to turning into clichés (tired, overused tropes); and this happens ever more quickly with Internet meme culture.

While visual clichés may be convenient shells for new memes, they usually bring relatively little meaning or feeling with them for most viewers, and thus aren’t really that interesting as subjects of remix.